– You were still at school during those years, weren’t you?

– No, I had already finished. I didn’t like school. It’s not that I didn’t do well there, but I couldn’t develop a liking for Latin at all. The PE teacher was a despot, always ready to tell you off. I used to tell myself “I need to do something to become better than him! So, when the law that made the school compulsory until 14 years old was passed, I thought about repeating the second year of middle school twice. To sum it up: I turned 14 on 16th June, on the 12th I finished school and, on my birthday, I went to work at my father’s.

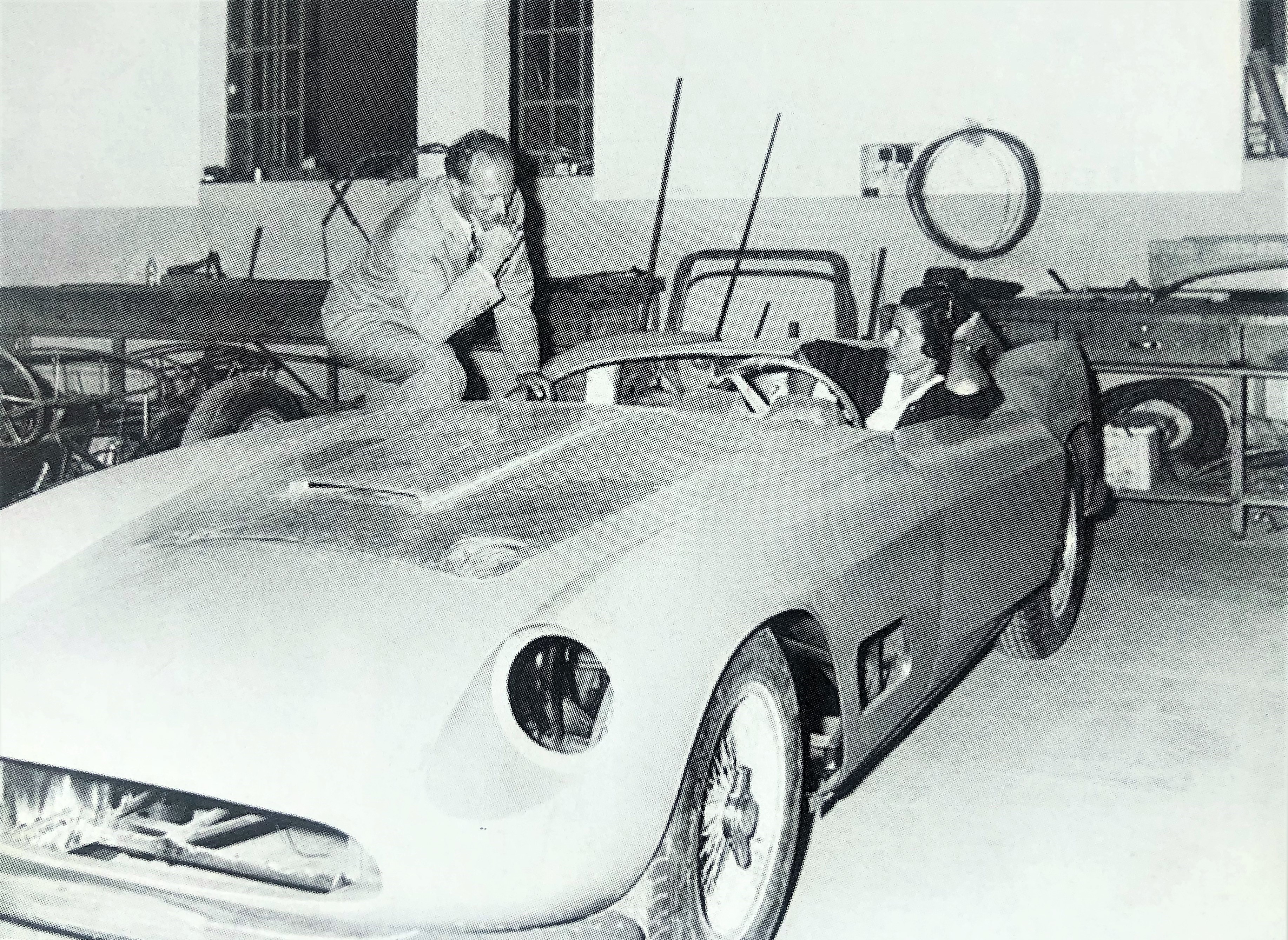

- Oscar and his father Sergio Scaglietti in the workshop, from the volume “L’ê andéda acsè” written by Franco Gozzi, Artioli Editore

– What was working in the workshop like, during the early days?

– What was it like? I was accepted like I was the resident idiot. The comment was: “Cretin, you failed the school year, come on… put the tyres on! Sweep the floor! Sort out the wood shavings!” We worked hard all day long, until the evening. There were some people who welded and had the blowtorch with the tubes, the gasometer with the silicon carbide in it, to make gas (because we made it), acetylene, oxygen… We had to close the taps, make sure that they didn’t stay open overnight and then we had to “wrap up the rubbers” so that the tubes didn’t twist.

– And did you do your best?

– I had to, otherwise, it was a big problem!

– What was your father like with you? Besides him reprimanding you for failing the school year, did he treat you as a son, in the workshop?

– Oh no, absolutely not! He constantly told me off, so that the others understood that there were no preferences. We had to do things well, there was no escaping that. When my father got angry, he kicked the bins hard and used to shout “you don’t understand a thing, you’re an idiot, I was right about that!” But I never saw him getting majorly angry… If he said “do it like this”, it meant that that was how we had to do it. And if something was wrong, I was the one that he shouted at in front of everyone. Well “everyone”… there were eleven of us back then. Not that many.

– It must not have been easy. How did you feel?

– How do you think I felt? Bad, of course. I never dared to contradict my father in front of the others. At home I did, often, we had discussions to justify our choices and to clear the air between us. If I was right, my father was the first to admit that. I thought: it’s hard to climb the ladder! Then one blow with Afro Gibellini, one with Giancarlo Guerra and one with Amleto… a day he put me to work as a help in the manufacturing department. How did it work? They gave me a piece of cardboard with the shape and I had to cut out the metal sheet. The masters used to tell me “Here there is a 1cm bend and you put it in this mask, then you hammer all around it” and so I already made the little pieces that the others assembled later.

– Do you mean your teachers?

– Yes. My first teacher was my father, a teacher in life and at work.

- Oscar and his father Sergio Scaglietti

– And what about the others, what were they like as teachers?

– Oh, they were anything but tender. When I made a mistake soldering, some of them burned the hair off my hand!

– Really?

– Yes, but each one of them helped me in their own way. Of course, the methods were what they were: a slap and that’s it.

– Would you have liked to become a panel beater? Or was that only a starting point for you, before you moved on to something else?

– I liked that, but I had something else on my mind. Beating metal isn’t easy, but you need to be careful not to put anywhere there is already too much of it, or not to remove it where it’s missing. The best tools are your eyes and your sensitivity of intuition, hearing if the hammering is solid or a tic, tic, tic. You know, there are some people who hammer too much, which is useless. The hammering needs to have a purpose: the hammer shouldn’t be stroked but dominated. However, as I mentioned previously, my head was elsewhere. What I really wanted was to make a car.

Playing with cars… all children started like that: with the car seen as a toy, a little like a first (rudimental) treasure. That is why desiring to make a car has a lot of meaning. It’s a sort of threshold, an open door on adulthood.

An obvious question comes to mind.

– What was the first car that you made?

– Well, I started when I was 14 years old and we made the long wheelbase California and the Tour the France. I made the California’s doors with Afro Gibellini, who, as well as Ferrari Franco, was in charge of making niches, small doors, air inlets and the mouth of the GTO. Then, I worked with Giancarlo Guerra and I learned to make the underbody, the shells… He knew how to make everything! I learned how to make the windscreen’s frames when they were manufactured over three pre-shaped and pre-cut metal sheets with adaptable development, because we bent the metal sheet when it was already shaped, and when it was finished, it was shaped like a cone. We made all of the different developments out of cardboard, with the first piece made, you adapted it to the mask, then you piled the development, you put it back on the metal sheets and you cut out pieces which were all the same and with the right development, so that when you bent it, it went to its own position spontaneously, without needing corrections, hammering or further soldering. Fiat already pressed that kind of metal sheets, but they wasted a whole sheet to make a frame, and it was a large sheet too. Whereas, as we cut out the developments, we placed one inside the other, therefore there was less waste. On the other hand, all pieces were cut out by hand: therefore, the labour cost was higher for the product, but there was a significant saving in terms of material.

- From the volume “L’ê andéda acsè” written by Franco Gozzi, Artioli Editore

– Roughly speaking, we got to the 60’s: the golden age for the Carrozzeria Scaglietti. I wonder how many important people came to you…

– Yes, in the 60’s I saw many of those: lucky people. Look at Marzotto, for example, an excellence within the weaving industry. You should have seen Marzotto when he came to our workshop, enthusiastic to see the metal sheets being hammered, he was very fond of cars. Another person who I remember in particular was Greg Garrison, TV producer and director, a friend of Frank Sinatra, of Sammy Davis Jnr, of Dean Martin… I liked him because he could make the artist, the oil company director and the politician roles all together. He enchanted me! In Montecarlo, he used to rent an attic and invite all of his friends, there were people there of all social statuses. He dealt with everybody. He could sell stuff to everybody and he had his own cut. He was a quick-change artist, and he made a lot of money. He had something like nine or ten Ferraris, all with personalised finishings and he lived on others’ work. I considered him to be a chameleon and that was what aroused my curiosity. I used to think to myself: if I could juggle between kings, princes, billionaires, politicians, actors!

I remember when Sergio made the Ippocrate’s car for the Mille Miglia, a Tour de France.

– Is Ippocrate truly his own name? It sounds like a stage name.

– It was actually his pseudonym: he used it so that his wife wouldn’t recognise him, as she would have never allowed him to race. This gentleman driver, the owner of the Timavo paper factory in Trieste, signed up for races with his stage name …. X car, without adding the chassis name and the registration number, so that even if his wife looked at the newspaper and said “look at this idiot” she didn’t realise that it was actually her husband! She read “Ippocrate” and she didn’t raise any problems with him. These gentlemen were my father’s first sponsor. Even Marzotto, before he went to Enzo Ferrari, used to stop by at my father’s “Sergio, I’m going to order a car, can you make it?” There was a friendly and human relationship between them.

- Giannino Marzotto at Mille Miglia, from the volume “L’ê andéda acsè” written by Franco Gozzi, Artioli Editore

– Can you mention a few names?

– Well, there were the singers: Mario Del Monaco, who wanted the personalisation, the golden nested initials in the steel knobs, which were handmade. I liked Del Monaco. I met him because he came here, to ours, dad took the California to his house. He lived right next to Tito Schipa. Actually, do you know that they used to call on each other singing, from one balcony to another? Yes, that’s right! When my father took the California there, Del Monaco called on Schippa with a high note to invite him to go and see the new car.

– Can you remember any other famous people?

– When King Leopold came with his wife, I saw him, do you know that? The queen was beautiful. I was also charmed by my father’s simplicity, who spent time with all of those people. He was the same Sergio as ever with anybody, and this is not something that everybody would do.

- King Leopold and Lilian de Réthy, from the volume “L’ê andéda acsè” written by Franco Gozzi, Artioli Editore

Oscar laughs.

– I have to tell you what happened with the doves!

– What do you mean, what happened with the doves? When the Belgian king came to try the California with the queen, my father, very politely, said “Come here, madam, I’ll let you try the seat. Here, this is your car.” Then, he started chatting and talking about the family, my father told them that my brother really liked carrier pigeons. Back then, we had a small dovecote in the company, which a dove enthusiast, kept racing doves for long and short races. Thus, the king sent his driver with a little cage containing two pigeons and he had it delivered to the workshop. When my father saw the cage he said “Oh, look at how chubby they are! Now we’ll give them to Carola to stuff them!” Everybody laughed, while the driver was alarmed: “Mr Scaglietti, these are racing pigeons! They’re not to be eaten, they’re the King’s racing pigeons!”

– And what happened to the pigeons?

– My brother and his pigeon enthusiast friend had them mating with ours and when we put the hybrid pigeons on the field, those which had been crossbred with the “royal” ones always came first.

- Oscar Scaglietti

– One day, we got a call. “We need to race in Mont Ventoux, there are forty days to go, please organise everything”. We got to work straight away, to put the team together to build the Ferrari 206 Dino Sport. We worked day and night for this prototype, which was smaller and lighter than the P1, 2, 3, with the engine of the Dino. The Cavallino restaurant was in charge of bringing us food every five hours: a pasta dish, a main course and a side dish. The team was made up of seven people, I was the eight: I worked as a panel beater. They assigned us shifts, we worked without a break for even 13 hours a day. The Knight Commander came to check the work and always gave us satisfaction: “Oh, you have already finished that!” He said every time. On the fortieth day, the Dino left for the mountain GP at Mount Ventoux and it came first… Ferrari, with Ludovico, won the European championship on that year.”

He smiles happily and a little touched. Scaglietti’s golden years, for Oscar also correspond with the years of his personal growth.

The apprenticeship comes to an end, it’s time to look to the future and to do that with an adult mind, also because the automobile industry is changing and you need to keep up with such changes: maybe looking beyond the obvious too. That is how Oscar momentarily moved to Pininfarina.

– That’s where I built most of my career, because the two “Sergios”, my father and Pininfarina, agreed on the fact that I was to grow as a corporate figure.

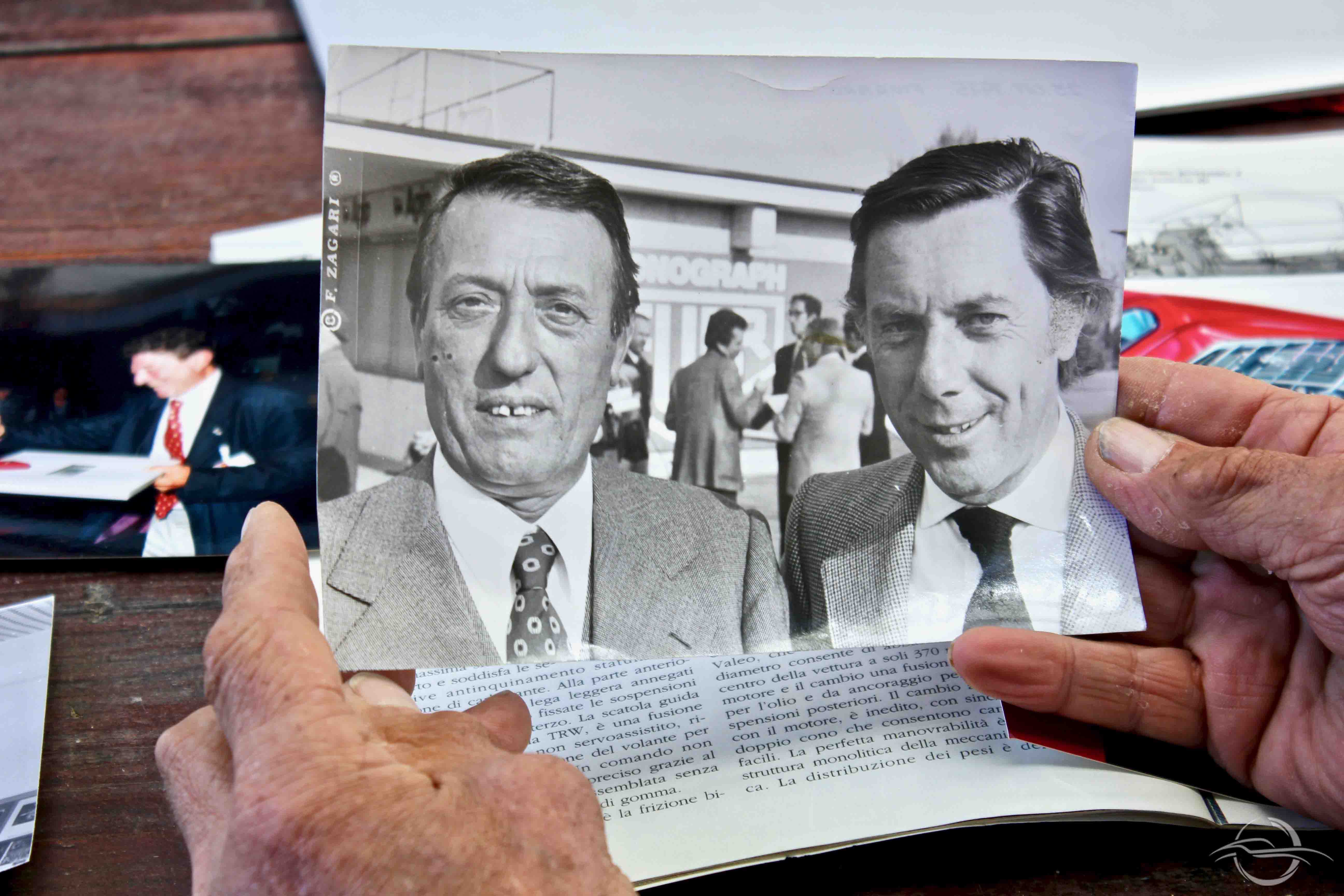

- Sergio Scaglietti and Sergio Pininfarina

At Pininfarina, they placed me alongside the general director: I had a very small desk in a corner of his huge office. It was curious that Pininfarina had introduced a small book, titled “the lexicon of bodywork”, so that they all spoke the same language. I still have a copy of it with me, that I keep with affection and nostalgia. I learned a lot during that period. I also attended many ergonomics courses, for example, how the worker had to move. I was often in Turin, even for eight days at a time, to attend these courses. I conducted studies about work, about how you enhance the value of a right handed and a left handed person, because designing and equipment need to take such things into account. A machine’s working process had to consider who is soldering and how the job is developed, you need to consider the different metals’ shrinkage, you might find defects by a few centimetres in soldering jobs, due to the width and thickness of the metal sheets. We understood that by placing at the two sides of the car a right handed and a left handed person, the soldering work was restricted and were symmetrical. That is, there was always a bit of shrinkage, but it was always symmetrical. Thus we started measuring shrinkage and experience lead us to creating parts which were upsized in function of their shrinkage, so that at the end of the manufacturing process, the chassis were perfect, just like in the drawing.

Oscar talks. He repeats several times that “starting to move around” made his fortune, he’s convinced about that and while I listen to him, he makes me think that this is one of the many joining points between yesterday and today. With a changing world in the background, the best strategy certainly consists of looking around, being open to change and renouncing the conveniences of your comfort zone. Between the experience at Pininfarina and at Fiat, Oscar learned several things which range between organising work and expertise in different areas

By International Classic, written by Martina Fragale

Keep following the story Scaglietti: “I want to make a car” – Chapter 3

Read also:

Scaglietti: “I want to make a car” – Chapter 1

Scaglietti: “I want to make a car” – Chapter 4

Scaglietti: “I want to make a car” – Chapter 5