The Electrofarmer

– I’m an electrofarmer.

He says that with a mix of pride and shyness, nearly as if he wanted to anticipate what I’m about to ask, and suggest the reading key to all of his history.

– An electrofarmer? How?

He brushes himself aside with a general gesture as if he had already said everything.

– Yes… an electrofarmer. Someone who is both an auto electrician and a farmer. My parents worked the land: I always lived with them and… I always helped them. When my father passed away, I carried on. Actually, I bought another bit of land. In Solara, you know? Eight kilometres away from here.

His red face, his blue eyes which smile seemingly friendly, behind a crevice: William Gatti looks younger than sixty-eight. His workshop is pristine and clean: it looks like the hall of a luxurious hotel. When I point that out, he looks towards his son, Christian.

– He’s the tidiness freak, not me!

Christian lifts his head and nods.

– That’s true. You should have seen the mess he used to work in when I was little: boxes, junk everywhere… What a disaster! He could actually always find everything in that chaos.

William Gatti doesn’t answer. He smiles to himself and he even looks a little proud in remembering the garage of his house, where he’d started working on his own from back in 1986.

That’s right, his house and shop: with his wife and children upstairs and him downstairs, lost between the cables and those systems which he reconstructed with passion and painstaking patience.

Electricity is a contained fire, blood which pulses impatiently in a car’s veins. An identikit which perfectly matches the first impression you have of William Gatti when you meet him: a contained fire which floods through every pore and which flames at the height of his face. It might be due to that passion that – he underlines several times – you need to put into everything you do: as much as in the care for the vineyard, and in the attention you put into giving the vital spark back to the classic car.

Today, he’s moved from his garage to the top floor – from rags to riches, as you say – the large loft of the workshop which he opened a little less than 10 years ago. And if at first glance the difference to the garage seems obvious, it is also true that in this movement of curtains there is a point in common: the need for concentration, rather than for isolation.

“I need silence to work – Gatti confirms – My son likes listening to the radio, but I cannot work with background noise. Luckily, we get on and he can hear well, so we found a compromise: he keeps his radio down and I work here, upstairs. You need concentration to create a system. Up here I do my own stuff… peacefully. On my own. I cannot do two things at once, also because you need all wires in an electric system. I mean, I always need to pay attention to the smallest of details: if I forget something, that means trouble.

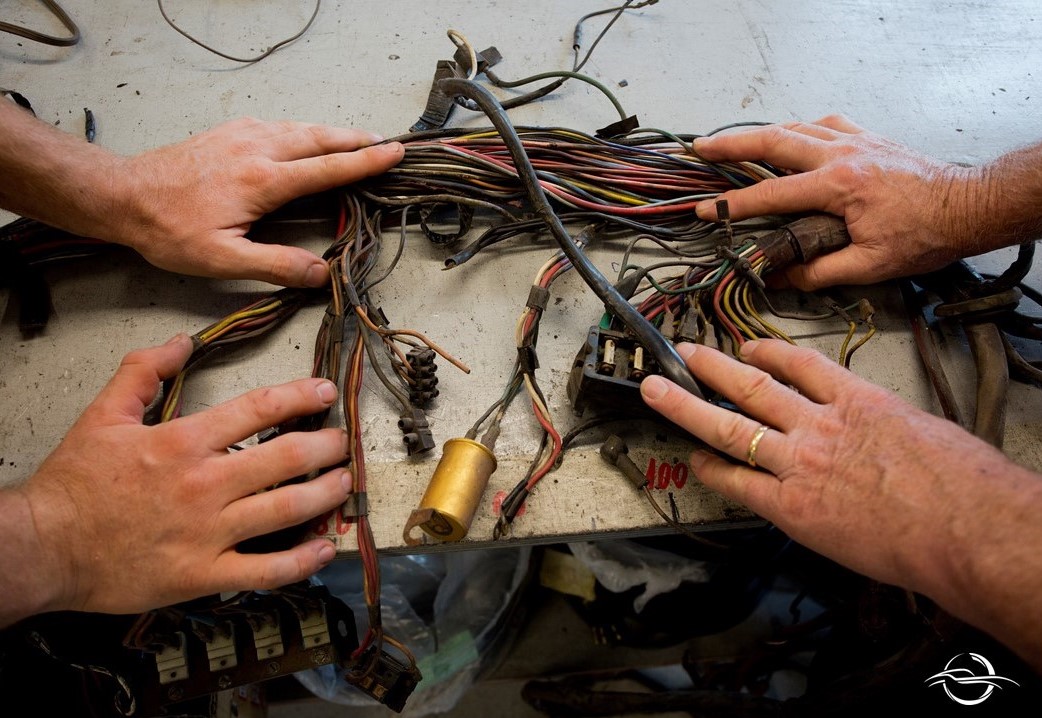

In fact, you only need to look at his workbench to understand that, when talking about the complexity of his job, he’s completely right. Just to be clear, it isn’t messy (you notice Christian’s input here too), but seeing an electric system like that, as if it was lying down on an operating theatre’s table, is enough to understand how articulated its structure is.

Multi-coloured wire balls are hanging from the walls. Christian tells me that when he was little when he went to his father’s garage with this friends, he used the wires to create bangles and actually – if you look at them with the eye of an amateur – those newly made electric systems look somewhat recreational. As if they were some giant Scooby Doo’s.

You only need to focus on a few details though, to realise that there must be a strict method behind the result, which has been established through the years. William Gatti nods. There is a method, but it created itself: a little like the vineyard, which grows and provides its fruit under his vigilant gaze.

– There are some systems which I’d already worked on in the past. In that case, I start off from the wiring diagram, which is downstairs… in the library.

– In the library?

– Yes, I’ll show you later.

– Are you referring to instruction booklets?

– No, cars only started to have their own maintenance booklet from the ’80s: previously there was no handbook. And, in any case, the handbook only provides you with an overall ideal, when you make repairs… reconstructing is something different all together. Downstairs, in the library, I have the wiring diagrams of all of the systems which I’ve worked on through the years. I start from there when I happen to work on a car of the same kind. I take the wiring diagram and… off we go! Everything is already there: measurements, colours of the wires and everything else. Whereas, when I happen to work on a car, which I never put hands on, I have a different approach: I need to have the car in my hands.

The wiring diagrams

Gatti describes an articulated process, which is conducted side by side with the other “actors” who intervene during the different phases of the restoration: the body shop mechanic, the mechanic, the upholsterer. The car arrives at William Gatti’s workshop in bare condition. Or better: it gets there stripped, deprived of any detail: it is stripped from the mechanics and upholstery so that it’s easier to extract its electric system. The lights and the dashboard are dismantled, afterwards, the dashboard is given to the upholsterer, who will upholster it from scratch. Then, the car is given to the body shop mechanic (who will take care of the metal sheet and to re-varnish it) and then, it goes back to Gatti’s workshop, with no engine nor interiors… with nothing but fresh varnish.

At this stage, William Gatti equips it with the refurbished electric system, which is tested out. Now the car goes back to the body shop mechanic and the other restoration professionals: the mechanic – who will mount the engine – and the upholsterer, who will upholster the interiors. An actual concert of work, which – Gatti confirms – takes quite a long time.

– In total, considering the different stages, the restoration of a car may even take years. Our job takes around a month and a half. And the job of the auto electrician is barely mentioned. Everybody thinks about the mechanic, the body shop mechanic, but let’s be honest: the car won’t start without the electric system!

The electric system, indeed: I ask Gatti to tell me how he creates a diagram when he puts his hands on a car for the first time.

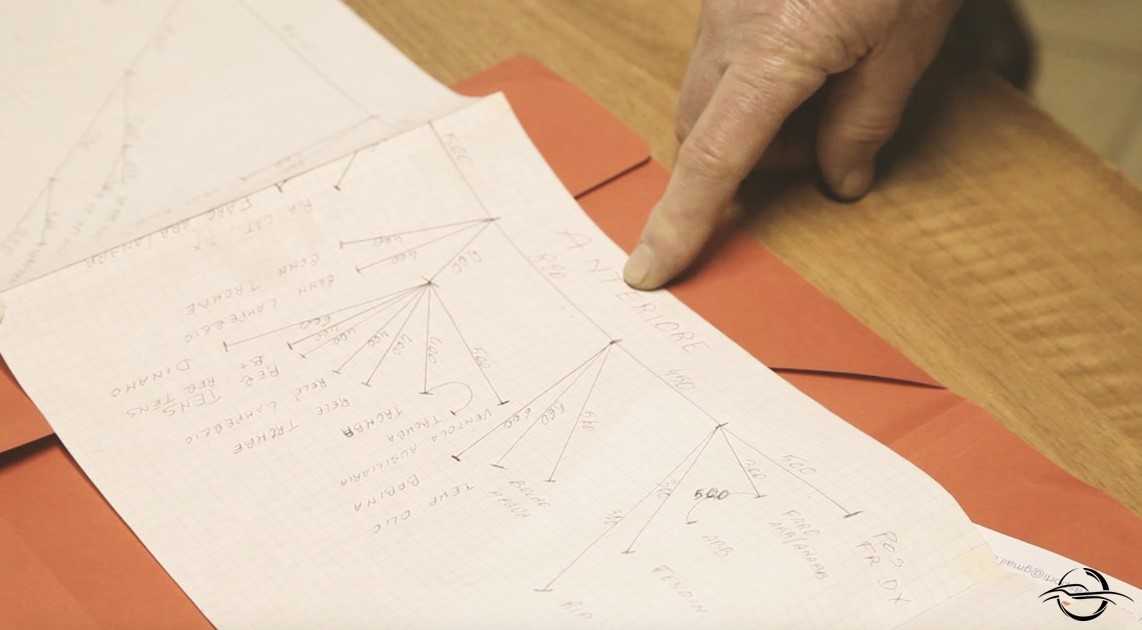

– First of all, we deal with extracting the old system, we lie it on the bench and we compare it with the wiring diagrams in our archive. Often, we need to re-make everything from scratch because each classic car is a world of its own. Once we compared the system with the wiring diagram, I trace the first drawing, with pen and paper. I include everything in the drawing: we take the measurements of the different cables, we indicate the function of each exit… Then we make the second drawing: the cut list. We take all cables, one by one (starting with the front ones, for the lights, to the dashboard) and we report everything: colour, length, diameter. Afterwards, I trace the third drawing: the large one, which you can see here, on the table.

– Is that the first life-sized drawing?

– No, here I only report the dashboard and the fuse block, which is the heart of the electric system. I make a large drawing in 1:1 scale and I work directly on that. As far as the rear and the front are concerned, I build them based on the first drawing and on the cut list. Afterwards, it’s about assembling everything: to join the parts into one. It’s a little like having a body, cut in several parts, lying down on the operating theatre table, with different exits: they need to be connected to the different veins. Finally, we proceed to the taping, we place the rope ends (that is, the iron junctions), we connect the wires to the fuse block and we add the different accessories (switches, buttons, etc.), just to check that everything works. Then, we remove them to mount them on the car.

– What about the wiring diagrams library?

– That’s right, the library… come with me, and I’ll show you.

I’m facing no less than the treasure chest. The “wiring diagrams library” is as colourful as the wires of the systems that William Gatti braids patiently. There are many red binders, with a ream of multi-coloured folders peeking out. In there, there are over forty years of history and experience, detailed radiographies of the venous systems of cars which made history… the same which appear on the workshop’s walls, with the drawings that Christian has traced with his experienced hands.

They’re historical cars, which Gatti worked on: Lamborghini Miura, Auto Avio Costruzioni 815, Lamborghini 350 GTV, Maserati A6G Frua… William Gatti points them out proudly, calling one by one by name. He does that as if they were something hybrid, half-way between a hunting trophy and a photo album full of memories. And especially, he does that as if – in a certain way – they were “his”. He’s a little like a physician when helping a new life coming to life is equivalent to taking its paternity, to a certain extent.

You would never say that everything started off with some cardboard boxes! William Gatti smiles when he tells me about it. It’s true, he always had a thing for cars’ electrical systems, but he took the road which leads him to where he is today fortuitously following logic based on the stricter practical sense – very farmer-like.

“You don’t want to study anymore? That’s fine”, his father told him, a clever man who didn’t choose to work in the fields but he had found himself doing it as if it was a too heavy burden to carry. He would have liked something different for his son, for example, that he continued to study.

But William didn’t want to know, and he attended only the legally compulsory schools: primary and junior high school. That was it. His father had taken the refusal without complaining and he immediately found him a job, working for a friend of his who made cardboard boxes. Deep down, he probably wished to flatten his path, so to avoid that he would end up being a farmer like himself. William indulged him, but he had never cut his ties to the land, so he continued to help his parents during his spare time.

“I continued to make boxes for six, seven years – Gatti tells me – Then, in 1970, a position became available at Scaglietti: I didn’t have them asking me twice! At Scaglietti, we worked on a chain. I started lying down the cars’ systems, then, I was lucky enough to have a boss who switched me to all the different stations. That is how I learned my job, on Ferrari’s of course, because at that time, that is all they did at Scaglietti.

In ’78, they moved our department to Maranello: I stayed there for 3 days, then I resigned. It was too far for me and I received an offer to go into business with a workshop close to me. That’s how I began to put my hands on other cars too, such as Maserati and Lamborghini. Then, I started to wander through other workshops, until ’86, when I became self-employed and I started working on my own.

In the garage of his house, a little like Steve Jobs, with the difference that, at the time, William Gatti, knew his job in every detail and he already knew exactly what to do. The systems were made at home (home-made, in the most honest sense of the term) and then they were taken to the location. The hard – but stimulating – life of a freelancer: you need to be born with talent, in order to accept its burden and lightness.

– A big difference to when I was a regular employee at Scaglietti’s. Please be honest, did you like working on your own?

– Well, yes: it was a clever and profitable method. However, the other side of the medal was that the end customer didn’t know that I had worked on their car. In any case, things went round, with their pros and cons. Years went by and I had already decided to shut down shop and retire. At that stage, my son arrived and he broke the eggs in my basket!

Father and son, history goes on

He went to Turin, to study car design. Then, they told him that in order to do his job, he would have had to go abroad, far away from Modena… and he didn’t like that at all. One day, I saw him arriving and he told me: “Dad, I’ll come to work with you!” What should I answer? Nothing, I put aside the idea of retiring and I got back on track. That is how, ten years ago or so, we decided to change our working system and we re-opened the workshop, here in Bomporto.

He went to Turin, to study car design. Then, they told him that in order to do his job, he would have had to go abroad, far away from Modena… and he didn’t like that at all. One day, I saw him arriving and he told me: “Dad, I’ll come to work with you!” What should I answer? Nothing, I put aside the idea of retiring and I got back on track. That is how, ten years ago or so, we decided to change our working system and we re-opened the workshop, here in Bomporto.

– Why did you do that? Was that to escape anonymity?

– Well, no, it wasn’t: it was for convenience reasons. It is difficult to work in someone else’s house because you may find a car in the cold or under the sun and you have to get on with it…

William Gatti will never admit to it, but I’m secretly convinced that there is a lot more than a pure and simple convenience issue behind his decision to open a workshop. The alchemical process, with which a Name is turned into a Brand – what, in “corporate” terms is called personal branding – presupposes an underlying reason: an awareness of your own professional identity. A process of individualisation which conflicts with some characteristics of the farmer humus, where, as well as Gatti, the majority of the artisans that you meet in the Modena area come from.

“When someone asked Enzo Ferrari why his factory was in Maranello and not elsewhere – Christian points out – he answered that here there are farmers and that no one is better than farmers in turning the matter of nothing and create great works of art, with their own hands and talent”.

That’s true. As it is also true though, that the farmer’s mind often wishes to remain anonymous, in virtue of a loyalty to their origins, which goes hand in hand with the intolerance towards those who tend to have too big an ego. Modesty is an obligation, just like how I notice when Gatti talks to me, with a reproachful tone, of his colleagues who tended to show off too much.

Flying is fine… as long as you fly low, with an eye towards the sky and one towards land.

He always fits within this same frame – the “obligated modesty” – which is inscribed into the artisan’s creative expression: a secret signature, left between the lines as if it was written with invisible ink. Because even the scrupulous job of the auto electrician presupposes a creative approach. William Gatti himself points that out.

– When I re-make an electric system, it happens that I put something of mine into it. It’s to do with making improvements: adding something which doesn’t attack the originality of the system, but which today is necessary to drive the car peacefully on the road and to have a minimal functionality. For example, the supplementary radiator vent. Or the emergency indicators.

Yes… actually, it is an actual restoration, strictly speaking. The confines between artisanship and art aren’t a wall, but a permeable membrane. Even when it is about restoring a car’s electric system, rather than a painting or a fresco. William Gatti is aware of that. Even if maybe he doesn’t know anything about the nineteenth-century squabbles between John Ruskin and Viollet-le Duc, about what (and how) is licit to restore, Gatti is the first one to pose himself the problem of the difficult balance between respecting the originality and adapting it to the passing time.

A problem, which, with modern cars, has lost its reason of existing from the start. To the extent that at the end, I have a spontaneous question: in the world of serial mechanisation, where the human role seems to become less and less necessary, what is the role (and the future) of artisanship?

William Gatti shrugs once more, with a peaceful smile.

– I believe that there is a future now and there will always be one. Classic cars are those which are made by artisans, both in terms of the bodywork (have you ever seen a metal sheet bent with a hammer?) and the electric systems made on a bench. And then there are the interiors, made by the upholsterer who knows the car and restores it to what it was like originally. That is our job: a world of its own. It ends where electronics begin. The key difference is that modern cars are made in sequence. Which means that they will never become prestigious items: you will easily find spare parts for them, even in twenty-years’ time.

Whereas, classic cars are a whole different matter. If we take the door of a Merak e we try to mount it on a different Merak, you will notice straight away that it doesn’t work. Classic cars are all different from one another, maybe even just in terms of small details, but this doesn’t change things. For example, when I deal with a Miura – besides the three different models – I always need to consider the fact that, at the time, things worked differently than they do today. I mean, one could get up one morning with an idea, and put it into practice: just like that, based on his own idea!

This is just to say that with classic cars you need to adopt a peculiar approach, which is a little broader: by taking into consideration the idea which went around at the moment of the construction. This is a general rule, not only for Miura, but also for Mistral… each car has its own history and it carries it with it, differently from modern cars. Just like a work of art.

- Pic by Angelo Rosa

I’m thinking about Walter Benjamin, who, nearly one hundred years ago, wrote his essay “The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction”, I wonder if Benjamin even imagined that today, the subject of the reproduction on series and the “loss of the aura”, would have been applicable to classic cars too.

But our chat comes to an end. Gatti goes back to the things which he cares the most for: his son who, (you can see it a mile off!) he’s bursting of pride for, and his land, who he tirelessly continues to work every weekend.

– But, I mean, do you ever rest? This question comes spontaneously to me.

He doesn’t get perturbed by it. Of course… for William Gatti, working in the fields is resting: he allows himself a holiday while his wife takes care of the ninety-eight-year-old mother. There is no mention of great holidays, for now. On the other hand, the countryside is there, waiting for him every weekend: it is always the same but yet, always new. With his grain, the sorghum – a round seed which is used to make feed for geese and hens – and of course, the vineyard. This is the land of Lambrusco, and William Gatti likes Lambrusco very much.

With the exception of the manual picking of the historical vine in the new land, Gatti has arranged things as modernly as possible, and the picking of the grapes has been mechanised too. It is strange to think that this man – a living and breathing monument to the values of manual skills – has peacefully opened the doors to modernity and automatism in his fields. But maybe this is also an underlying prejudice. Past and present coexist with two historical tractors – one is a Landini and one is a Gualdi – which Gatti talks about as his pride and joy. And which maybe, act as a red thread between the world of cars and the fields.

When William Gatti leaves, he gives me a jar of honey from his fields. “It is millefiori”, he specifies. His father left him the hives after developing an allergy to bee stings, and he cares for his bees, and the fifty kg of honey that they give him every year.

I look at him as he leaves, straight as a dime, proud of his cars, of his vineyard and of his protruding belly which he cultivates with the same care. “Once, they told me that anorexia is a bad disease. I do my best to fight against it!” He smirks as he says that.

Happy, poised: a man who oozes electricity from each pore. There isn’t anything nervous about him though: his flame is mature, tempered through the years. It is the ace in the hole – or the brand name – which distinguishes a common auto electrician from William Gatti. The Electrofarmer.

By International Classic, written by Martina Fragale