– What was the collaboration with the designers like?

– The collaboration with Bertone was a little different to the one with Pininfarina. With the latter, we talked about drafts, then on the mannequin, then on the breakdown of parts and we always found an agreement: we were very much in tune. There wasn’t the same dialogue with Bertone regarding the post-drawing or post-mannequin.

They delivered the mannequin made in a certain way and they asked for the changes to be as little as possible. Which wasn’t always easy: it happened that this caused us difficulties in developing the project. Sergio Pininfarina always came with two collaborators: they were Fioravanti and Ramacciotti, there were three or four of us too.

- Sergio Pininfarina and Lorenzo Ramaciotti, picture taken at the Ferrari Museum in Maranello

Before we presented the mannequin to my father, to the Knight Commander and the managing director, Sguazzini (or someone else on his behalf) we had already worked on it. We also discussed about any possible changes and we found compromises which made by the designer and us, who needed to create the cars, happy.

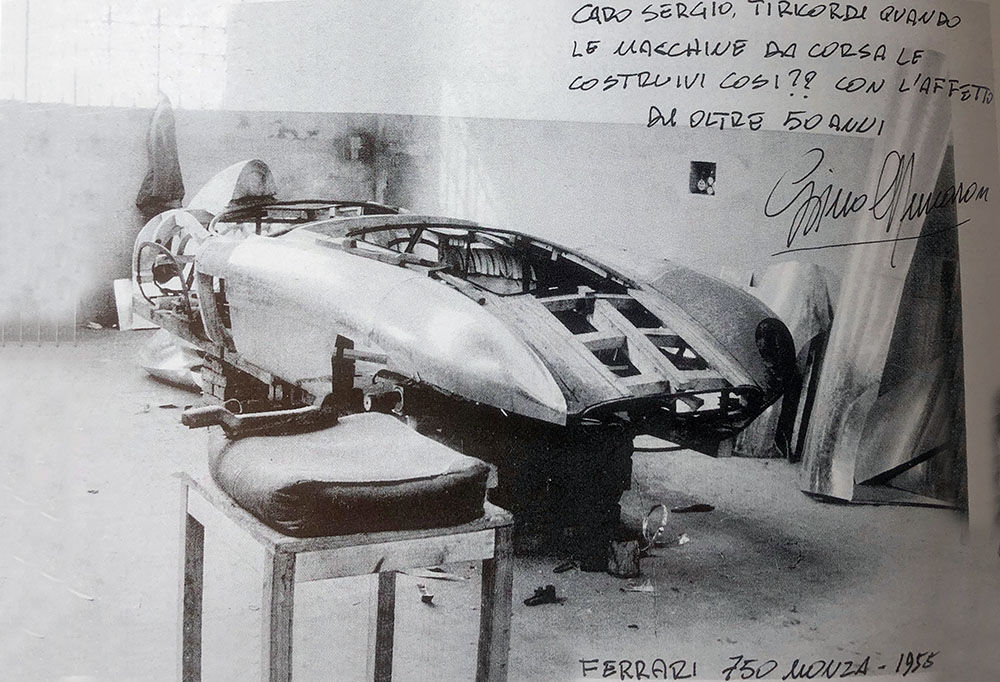

- Ferrari 750 Monza mannequin, from the volume “L’ê andéda acsè” written by Franco Gozzi, Artioli Editore

At Bertone, they reasoned in stagnant departments, there were many steps, with the project which had to be chosen and accepted by the designers, the management… Yes, sometimes it was very hard for us to fit everything needed under the bodywork! With Bertone, we were involved when the decisions were already made… however, they were both very constructive experiences.

- Giuseppe Bertone, picture taken at the Ferrari Museum in Maranello

During those years, Scaglietti was all but a backdated company: quite the contrary. In terms of working method, Sergio was exactly on the antipodes of the centralising patriarchal model: for example, often, he gave extra work for his employees to do at home, thus stimulating the creation of small teams which interacted, experimented, found solutions. This was something truly avant-garde for the time, which was more in line with some more modern forms of corporate organisation: which are less focused on the vertex, which stimulate self-empowerment and proactivity of the working teams.

Oscar remembers everything in detail.

– Amongst the extra work that my father assigned to his employees, there was the construction of the seats’ boning or the coverage of exhausts. When the catalytic converters’ problem had arisen, we placed rock wool around the kaolin tubes, and over it, we used an aluminium coverage so that the wool didn’t flake apart. The windscreen and back window’s frames too, they took the brass bars cut to measure home, they bent them on the dolly and we received the parts soldered and ready to be chrome plated and mounted. Whereas we had OMZ, Officine Meccaniche Zanassi, make the windscreen’s threads, they were right next to us. OMZ made frames for briefcases and electrical ballasts to be placed inside the fuel tanks, to heat up petrol. It was a nice company, which bent the aluminium and steel frames for us. That is how we created an actual network around Scaglietti’s, in San Lazzaro.

He talks proudly. For those who were born and grew up during those years, the development of the territory goes hand in hand with the business development.

– As I mentioned previously when I started working at Scaglietti’s, there were twelve of us, myself included; when we sold it, there were approximately 280 of us. Yes, it was a family business, but it was also a business which looked forward, with the goal of growing and improving, thanks to small working groups which put a lot of effort into the work. The company grew side by side with experience. We had to create the network, there were no small companies suitable to build special parts for cars. The craftsmen around, back then, were the blacksmith who could fix your agricultural cart, who made window bars for houses or a scaffolding, but the blacksmith who could make parts for racing cars… well, they didn’t exist! The car industry also led to the development of the technology parts’ network here in the surrounding area, because in Correggio we had suppliers who went from being small ABS printers, who made pen caps, ended up making nails for the Shuttle. Yes, seriously: to attach plates, when the Shuttle went back, the nails were in peek-carbon. It is a plastic material which resisted up to 2400° C. Here, in Correggio, we did things that you can hardly believe. Can you think of it? Us and the engineering department made parts for the Shuttle! Yes, that’s right: the Hubble telescope has parts made by the engineering team. We went a long way, over the years. We went from hammers, soldering by hand to using robots, lasers and such things, we saw all of the evolution happening and we had to learn.

It is a growing setting. However, it isn’t anything frenetic or shocking. Based on how Oscar talks about it, it seems like the territory, as well as the Carrozzeria Scaglietti, translated the old rhythms of the land into that substantial innovation period too, and that is how the evolution took place: in a people-oriented way. For a happy paradox, the company is still a family-run business anyway, even though it’s so technologically advanced.

– When someone got engaged and introduced the fiancée to others, when they got married, it was truly a celebration for us all. We lent a hand if someone was unwell, my mother took the wives to the doctor… It was a different world all together. During our lunch break, we played football or cards, because there were two groups. Gian Carlo Guerra always wanted to win. Afro kicked him in the shins. We ate quickly so that we could play Briscola (one of Italy’s most popular card games), or football, then, Adolfo Bertacchi started playing the referee and he ruined everything. With Adolfo, I had a deep and loyal friendship. They had football tournaments against Maserati and Ferrari. We were the Scaglietti team. There was always a company rivalry during the workshop’s tournaments. There was a tournament where all of the workshops in the Modena province challenged each other. Then, the companies, such as Fiat, ended up hiring professional footballers to win… and we paid them!

When Oscar talks about cars, he lights up.

- On the left Sergio Scaglietti

– My father was bright, smart, genius… because one who isn’t, cannot concoct together such solutions, on two feet. Sergio and his team were the experts of improvisations which came up during the journey. My father often told me about the mad night of the Modenese car racings, that is how he named it… it was one in the morning and they finished the car that had to participate in the Mille Miglia. Gianni Sighinolfi, the test driver, went to test the Ferrari in Serra Mazzoni. But there was something wrong. During the descent, the four mudguards burned, the varnish was cooked and the tyres were all worn out on the edge, the buffer was caved in and the wheel was touching the mudguard. The car’s drawing called for dampening of six centimetres, but it didn’t say that the rubber buffer touched the mudguard. They needed to find a solution, fast! Sergio, Afro and Oriello cut out the mudguard and hammered it: to use our terminology, they made it grow. Then, they sprayed it with colour… and there we go, at 4:00 AM, the car was on the road to Brescia, bang on time for the competition at six in the morning!

– Fantastic! Come on, tell us a few more secrets.

– I cannot tell you about secrets, but I may tell you something curious: not all know that Carrozzeria Scaglietti has also built the body for a Chevrolet Corvette Coupé… we made four of them, we had 4 chassis, four cars, 3 were finished and one went half-finished. I helped Giancarlo Guerra to put all of the parts in the box to send them to the USA.

– And what about the Ferrari 250 Le Mans?

– Oh, that was a real hassle: all new to be made, with constructive issues which came out constantly. It was the first GT car. It wasn’t homologated as a GT because the FIA kept the prototype… Enzo Ferrari had a massive argument for that reason. The Ferrari 250 Le Mans won the 24 Hours of Le Mans, in front of official prototypes of all teams, that was a great satisfaction.

Oscar Scaglietti expresses once more his joy for that victory “We bet on Ford, which turned up with a 7-litre engine!”.

The winning 250 Le Mans bore the NART colours and it was the protagonist of a real mystery. Oscar doesn’t mention it, he’s a practical man: no gossip! While his eyes light up for the memories that he has “We got on very well with Chinetti’s team. We fixed Masten Gregory’s car with the American bodywork mechanic. It was a major gratification: He and I fixed it and the car came first overall during the race. During the dinner, Gregory told us: ‘Here, this is for a coffee on your way home’… It was a lot more than a coffee, he gave a massive tip to all of those who were in the pits and helped him! It was a surprise which left us open-mouthed, we all looked like princes!”.

The memories continue to flow. Oscar talks about the Ferrari 250 SWB: his actual first car, which was born “from a collaboration” – as he underlines several times – and which he followed from the first to the last hammer hit.

– When I started, we had set up the short wheelbase. That decision was made due to a technical requirement, to improve its driveability. Then, with the short wheelbase, we improved the connection between engine, gearbox and transaxle. That car went through a whole evolution, also mechanically-speaking.

– What do you mean?

– The steering boxes were changed from having an arm/gear to being made with a steering rack. The drivers felt it a lot better when setting it up.

– Which years would that be?

– It was around the ’60s, more or less. My contribution was minimal: I had to search for small details, I worked on the weights of the bonnets and boots. I always worked with the team: we used smaller tubes, such as aluminium extrusion tubes rather than solely boxed ones. We made a few improvements. Up until the Ferrari 250 California, the little wings were cut with the hacksaw, we made them by hand. With the Ferrari 250 SWB, we had the mould made to shear off the joints of the cooling foil. We were beginning to have more skilled workers. After the working hours, we sat around a table and one said: “I thought about making the part like so” and he brought the modified part, the other one said: “I made it this other way, I removed a soldering and I made a little fold in several points, etc.”, and we decided to try to make five or six of them, at the end of the working hours. Everything became easier and cheaper like that: by working on improvements in our spare time, all together.

- Ferrari 250 SWB

– Let’s take a step back: how did the manufacturing process work, from the drawing onwards?

– Fioravanti made a few drafts, from then onwards, there is a very close collaboration. Then, the drafts arrived at Scaglietti’s. We made a drawing in 1:5 scale so that there was a front, side and rear view. We started drafting up and, in the meantime, the technical office reported that drawing to the 1:1 scale. The draft could vary, Fioravanti allowed us to modify it. Sometimes, the final drawing was made when the cage was also finished. Over the years, the 1:1 scale wire frame model was replaced by the maquette, first with wooden ribs, then in ureol, which enabled the Knight Commander to get a sense of the finished car. In any case, at Pininfarina, they took a chassis and they created the edges of the car with iron rods, which was a 6 or 8 or 5 mm iron rebar. Afterwards, we put down the key points of the car: the wheel (back then, one of the workers created the round wheel edges, you created the edges of the mudguard), then the bonnet, the other mudguard… and that is how you created the first rib of the car, which was also at the centre of the front wheel. With the rods all soldered one to another, you created the whole profile, you fabricated a cage with the three rods and then all of the various sections at the centre.

- Leonardo Fioravanti, picture taken at the Ferrari Museum in Maranello

That is the reason why, in the end, there was the draftsman, the team leader with experience who followed the drawing, the final designer who had to approve the project. That is how it worked: the draftsman made a drawing, then he passed it on to the workshop and they analysed it, they started to create the part. Sometimes, the part was very complicated, but if the worker was actually there with you while you drew it, ready to improve it even before it reached the workshop, that made everything much easier. We set up the whole company to work divided by islands and smaller groups, we were the first to stack the doors at the side ready to mount.

– How did you do that?

– We prepared the finished doors and we placed them in a row, next to the car, where they needed to be assembled… that’s it. We had disabled people who worked from a sitting down position. At the Turin exhibition in 1959 or 1960, I saw a documentary with my father about the company Ford, which was organised, and we wondered: who is this Henry Ford?

– The Ferrari 250 SWB, was the car where I tried to introduce my ideas which I learned at Pininfarina. We built it with the method of productive sub-systems, that is, the roll-bars part was placed behind, with the back window, then there was a mask to create the sub-group; while the front part, the sub-frame and all of the interiors were made with different equipment. Basically, they were cars which were manufactured as if they were flagship models: they were precise, perfectly reliable, but made with a sub-system.

- Ferrari 250 SWB

– At a certain point, your father decided not to manufacture unique car specimens anymore, but to switch to series, is that what you’re referring to?

– Yes, small well-made series, which were car batches: no longer the usual four prototypes which we made over the course of one year. It was a big challenge. Basically, it was about making up to four cars per day, which had to be well-made. In the company, that meant stimulating a true and actual change in mentality.

– It was about broadening the clients’ spectrum. In a certain sense, it was also about changing their mentality. Your father was truly “forward-thinking”.

– My father, as well as Mr Ferrari, who suggested to make a few specimens and not to make cars all of the same, from the first to the last, because times change, just like needs, technologies and materials. There was always something new. Therefore, for example, we created the first series with the lights made in a certain way, the second series was made with hidden lights, etc. I mean, we continued to modernise our cars.

– Then, the series became larger, because they went from 50 specimens to 120-130 specimens before we started creating the second version, which was the same model with just a few changes. For example, the first series had a small back window, the second series had a large back window… only the GTO’s were 38-39 cars in total (prototypes included), there are 32-33 made in one way and then six or seven made in a different way. I mean, there was always an improvement, even if small.

By International Classic, written by Martina Fragale

Keep following the story Scaglietti: “I want to make a car” – Chapter 4

Read also:

Scaglietti: “I want to make a car” – Chapter 1

Scaglietti: “I want to make a car” – Chapter 2

Scaglietti: “I want to make a car” – Chapter 5