The Queens in the hands of Gian Carlo Guerra

– The Ferrari 250 TR? I made it, just like I wanted it to be because you know… I was a bit of a rebel. I mean, I liked doing things like I wanted to. When I made the 250 TR, I liked smooth lines, with no rungs or steps. A little due to a good taste: the car is a little like a woman and I don’t like pointy women. Then, apart from that, even if I’m not an aerodynamics engineer, I was well aware that, if you create a nice smooth section, the air goes around it. And I was right. When we tested it, we couldn’t even hear the air rustling around the car! I also built the 500 Mondial.

– What do you mean that you made it? Do you mean that you drew it?

– Yes, with the thread.

– What do you mean, with the thread? Didn’t you draw it at a table?

– No! I didn’t study drawing: I never had such skills. You know, I only attended school up to primary five.

– Okay, but how do you draw a car with a thread?

Gian Carlo Guerra smiles. He will tell me in due time. However, what is immediately clear is that the man who’s standing right in front of me has created the legendary Testarossa, the Mondial and the other lines protagonists of the racing cars’ season. Even though – just like he often repeats – he only attended school up to primary five, Guerra is very capable of designing. The fact that even the place where he now lives with his wife, Maria, was “made” by him, in terms of designing, is a proof of that.

– I drew and beat the roses on the gate, yes.

- Pic by Tommaso Ferrari

I designed the house when I worked for Scaglietti. I even built the plastic model for it, but then we put it in the attic and it came apart. We came here in 1949. As mentioned, at the time, I worked for Scaglietti and, on a Sunday, rather than resting, I studied solutions for the house. We were an assembly chain, my wife and I: she heated up the pieces and I bent them. We made this house together. Maria really wanted it to be a big house. We hoped that we would have a child, but that never happened in the end… so the house remained big: we had some dogs and a cat to fill it. Did you see the ground floor? They are my wife’s quarters.

Maria nods, with a look of understanding. She’s a slim and energetic woman. She harbours her husband with a rough and warm affection, just like a woollen jumper. The Guerra husband and wife, this year have celebrated sixty years of marriage and the complicity which binds them is visible. A house which was dreamt up and built by two. “An assembly chain”, just like Mr Guerra defined it. The poetry of simple things is never prosaic.

The years, sharing a whole life together, certainly matter but I think that deep down, the creative aspect also counts. Nothing pretentious, of course: when I ask Guerra if he considers himself to be an artist, he answers with a sharp and surprising “No, I did not study”.

Gian Carlo and Maria’s creativity is solid and concrete. What is nice must be firstly useful: you cannot escape that principle. Maria is a seamstress, she sews clothes and wedding dresses. And deep down, Gian Carlo worked as a tailor too. With the difference that, while his wife dresses people, he’s dressed cars all of his life. Born and bred by the team Scaglietti, Ferrari, Stanguellini, Lamborghini… I cannot stop looking at his hands and ask myself how and where, the 86-year-old man who’s standing in front of me, became the extraordinary panel-beater who everyone remembers.

- Pic by Tommaso Ferrari

– No, I didn’t learn to beat the metal at Scaglietti’s. My master was Onorio Campana.

Gian Carlo Guerra started working when he was nine years old. And he did it with all of the enthusiasm of a child who can absorb, take in and metabolise what he receives. He learned a job from Campana, and he preserved it. Actually no, he turned it into art, but in the etymological meaning of the term: the one that means doing, producing. With creativity, of course – and Guerra highlights this every each time that he hints at the rebel tendency of “doing things his own way” – but also with concreteness and solidity.

– In the evening, we went to Modena where there were the cars’ chassis, to beat the metal until late at night. Sometimes I got back home at two in the morning and my mother was there, waiting to undress me and send me to bed. I started with racing cars straight away, at Stanguellini, and then at Scaglietti’s, I continued on the same track.

– How did you get to Scaglietti?

– Through a friend who worked there as a varnisher. Sergio and I understood each other straight away: he was a good, amiable man.

Even if he doesn’t say that openly, what Guerra lived in first person is an epic time for Scaglietti’s body workshop. The moment of the take-off.

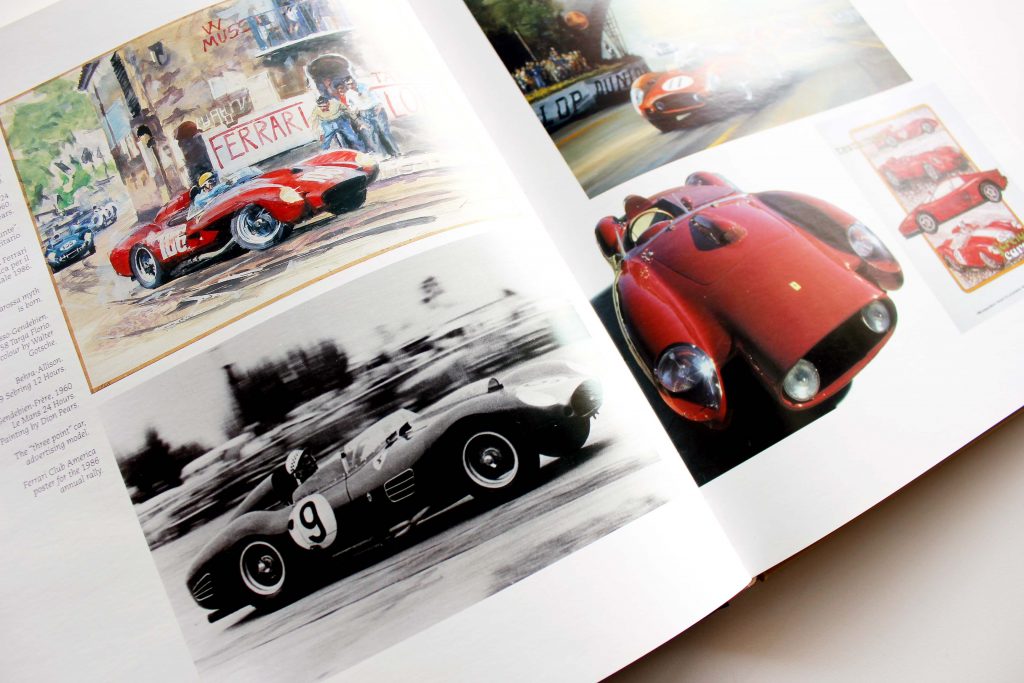

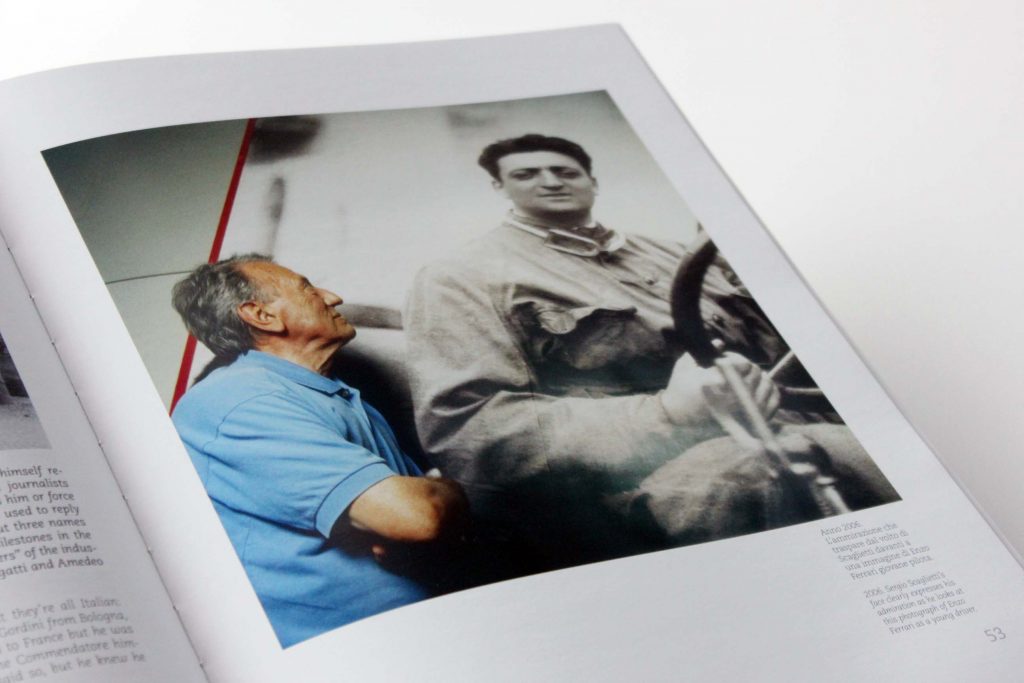

- Pic of the volume “L’ê andéda acsè” written by Franco Gozzi, Artioli Editore

Sergio Scaglietti started to work a few years before, at his brother Gino’s workshop. Then, on a fine day, he decided to “dive in” and take the big step. He certainly had the talent and by his side, he had two partners ready to help him along: Francesco Marchesi and Lino Sala. And that is how the mythical Scaglietti was born, in a warehouse rented for the occasion in Via Monte Kosika. The workshop dealt with repairs and it has around fifteen employees. One of them was a very young Guerra.

Things worked, initially quietly and then… Then suddenly they got the chance to truly show their value. It happened by chance, actually: just like in fairytales: It is 1953: one day, Scaglietti receives a new client. It is doctor Cacciari, a racing enthusiast, who arrives at the workshop with a Ferrari in particularly bad shape, which, however, against any prediction, the Scaglietti team manages to fix, nearly creating wholly new bodywork. The car – reborn – gains the attention of no less than Enzo Ferrari, who personally goes to Scaglietti’s to meet Sergio. This is the beginning of a collaboration which will revolutionise the fate of the workshop.

- Sergio Scaglietti from the volume “L’ê andéda acsè” written by Franco Gozzi, Artioli Editore

During the years that follow, the most loved Ferrari cars are born. Timeless cars, actual masterpieces. 500 Mondial, 750 Monza, 860 Monza, 290 MM, 500 TR, 250 TR, 250 GT California, 375 America, 250 GTO – Ferrari’s iconic car – 365, Dino… Each name represents a story: during the golden years, the Maranello’s forge achieves success after success.

Guerra is just as good and he actively participates, together with the Scaglietti team, in the making of the bodywork of cars which will make history. Working on a racing car implies the inevitable, being able to create ad-hoc solutions, to create something on your own two feet to fulfil the car’s potential as well as the international racing regulations. Rules which, as a matter of fact, change each year. For example, in 1957, the bodywork of the Testarossa 500, which was the natural prosecution of the Mondial 500, was lowered and narrowed, in order to be adjusted to the Annex C of that year’s international regulation. The car was then renamed – for that actual reason – Ferrari 500 Testarossa C.

By International Classic, written by Martina Fragale

Keep following the story Ferrari and Lamborghini – Chapter 2