Autofficina Sauro, a history of passion

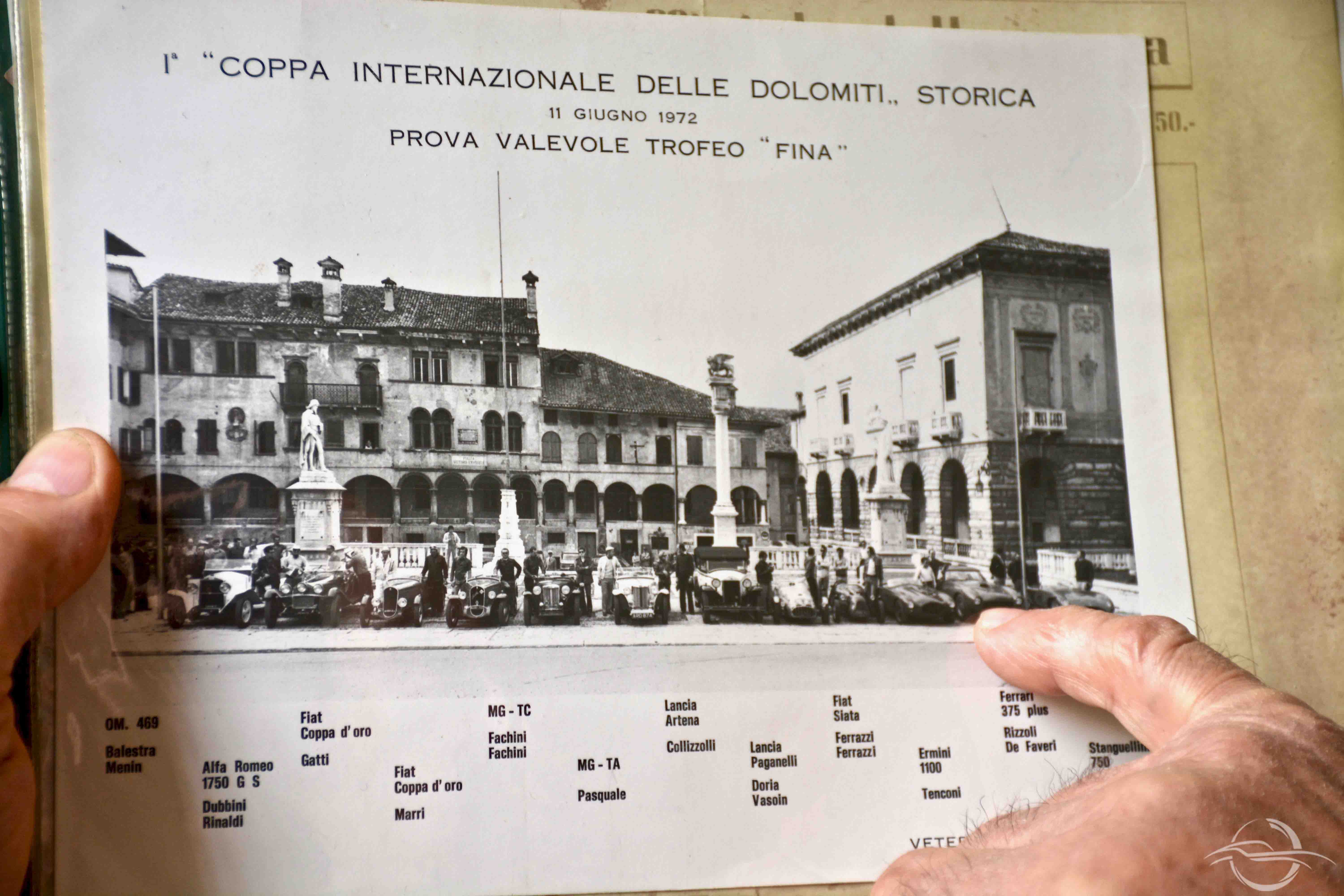

– Here, in this photograph, we’re amongst the first 12 qualified at the Coppa D’oro delle Dolomiti, in ’72, the people that you can see here, are the very same that started the Mille Miglia Storica…

- Coppa D’oro delle Dolomiti 1972

A dear friend of mine from Padua, Giulio Dubbini, used to organise it. They didn’t want us in Cortina, because they thought that we made the place smelly and dirty. So in the end, the mayor in Feltre hosted us (can you see here? This is Feltre town hall’s square). Then, we went from twelve to forty, fifty… and thus, Cortina understood that they could at least use some hotels since we brought tourism to their town.

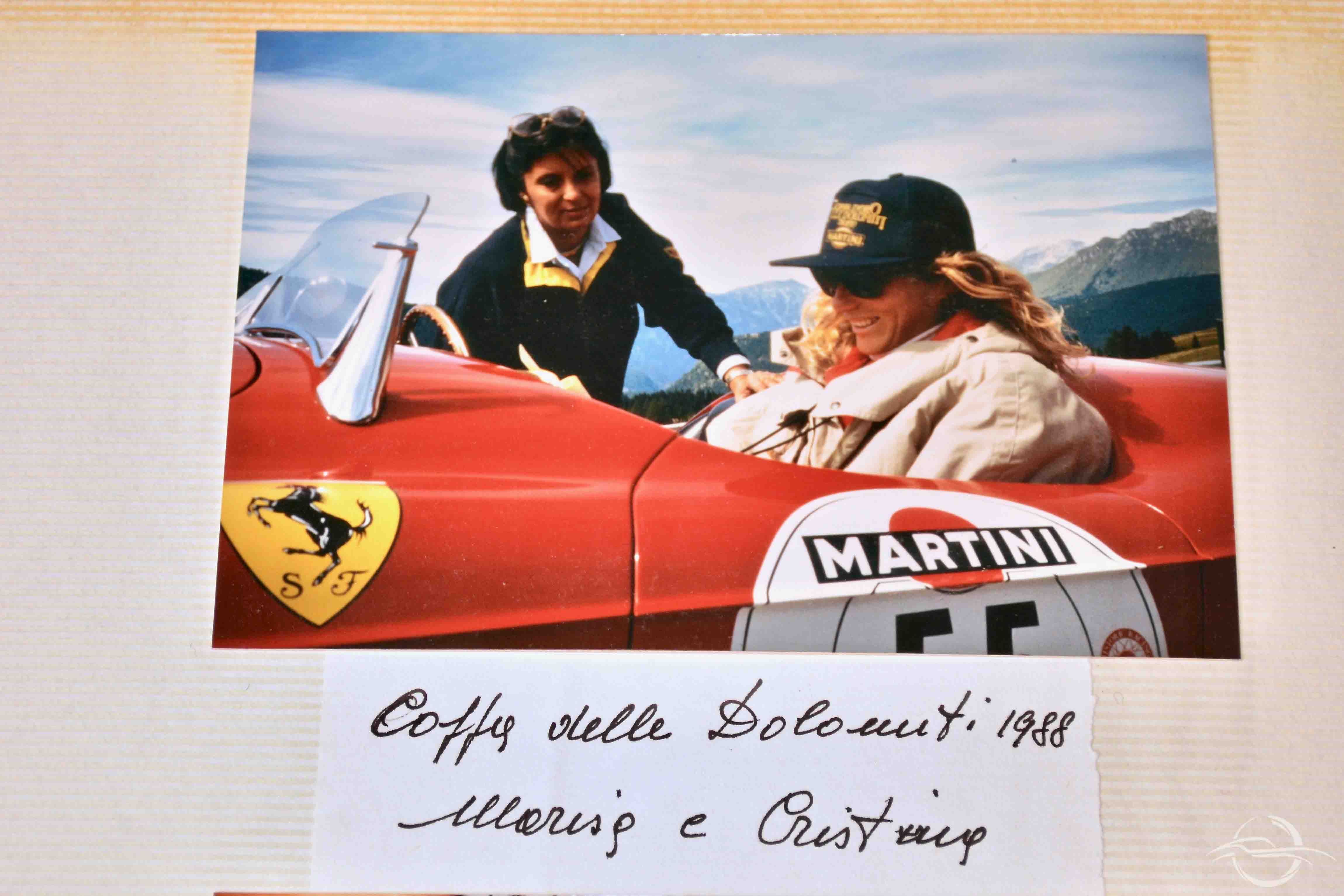

This is my wife, Marisa

- his wife Marisa and Cristina Segafredo

I lost her ten years ago. I owe everything to her: she gave me the chance to fulfil myself through my job. Marisa was great, she took care of the house, the children, of everything. I used to tell her all the time: “If there is another life after this, I hope I’ll meet you again.” She used to look at me, smiling, and do you know how she used to answer that? “I’ll think about it and I’ll let you know. You make me work too much.”

Luciano Rizzoli’s eyes are watery while he tells me about this. His workshop is an osmotic universe, where different things live and mix with each other.

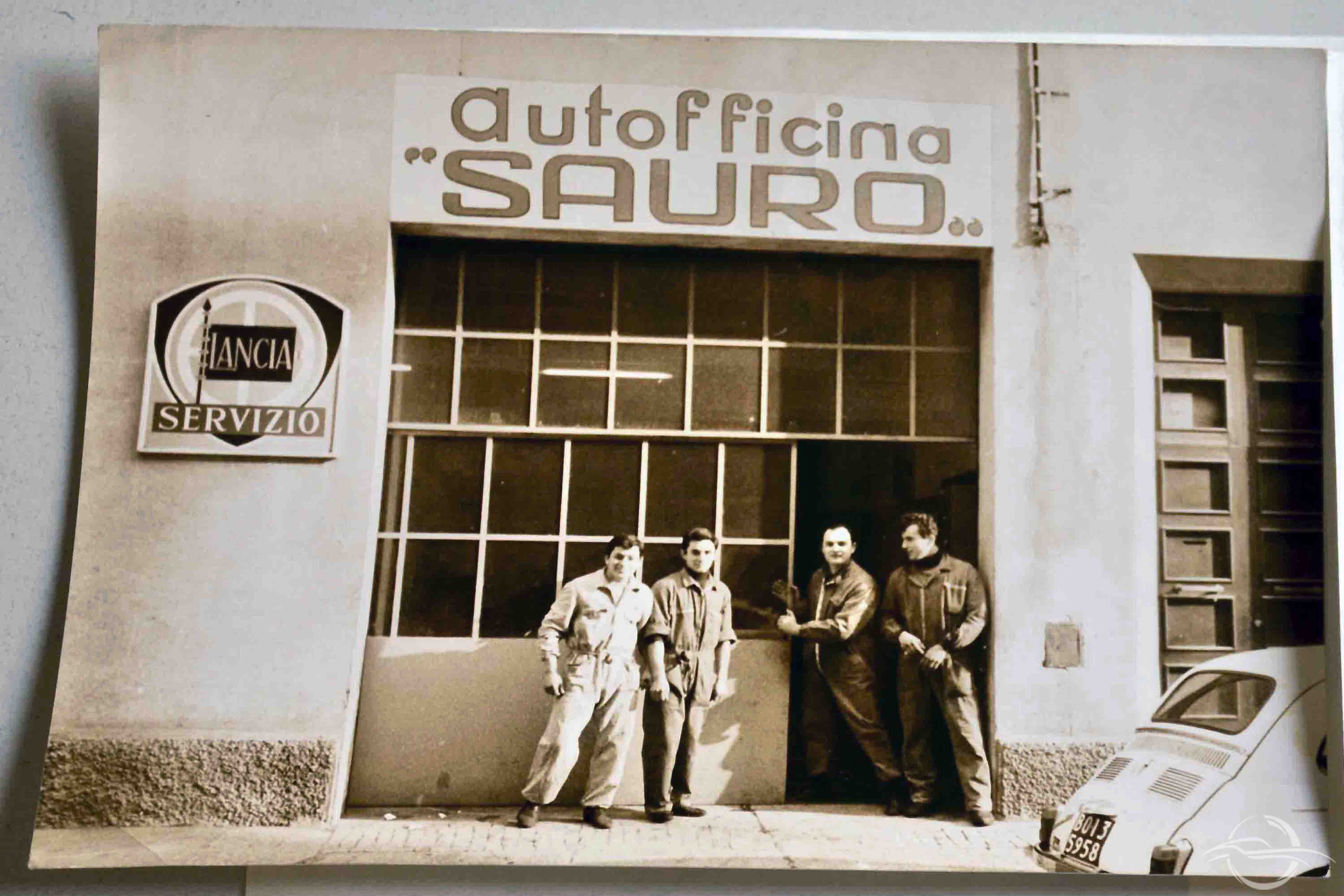

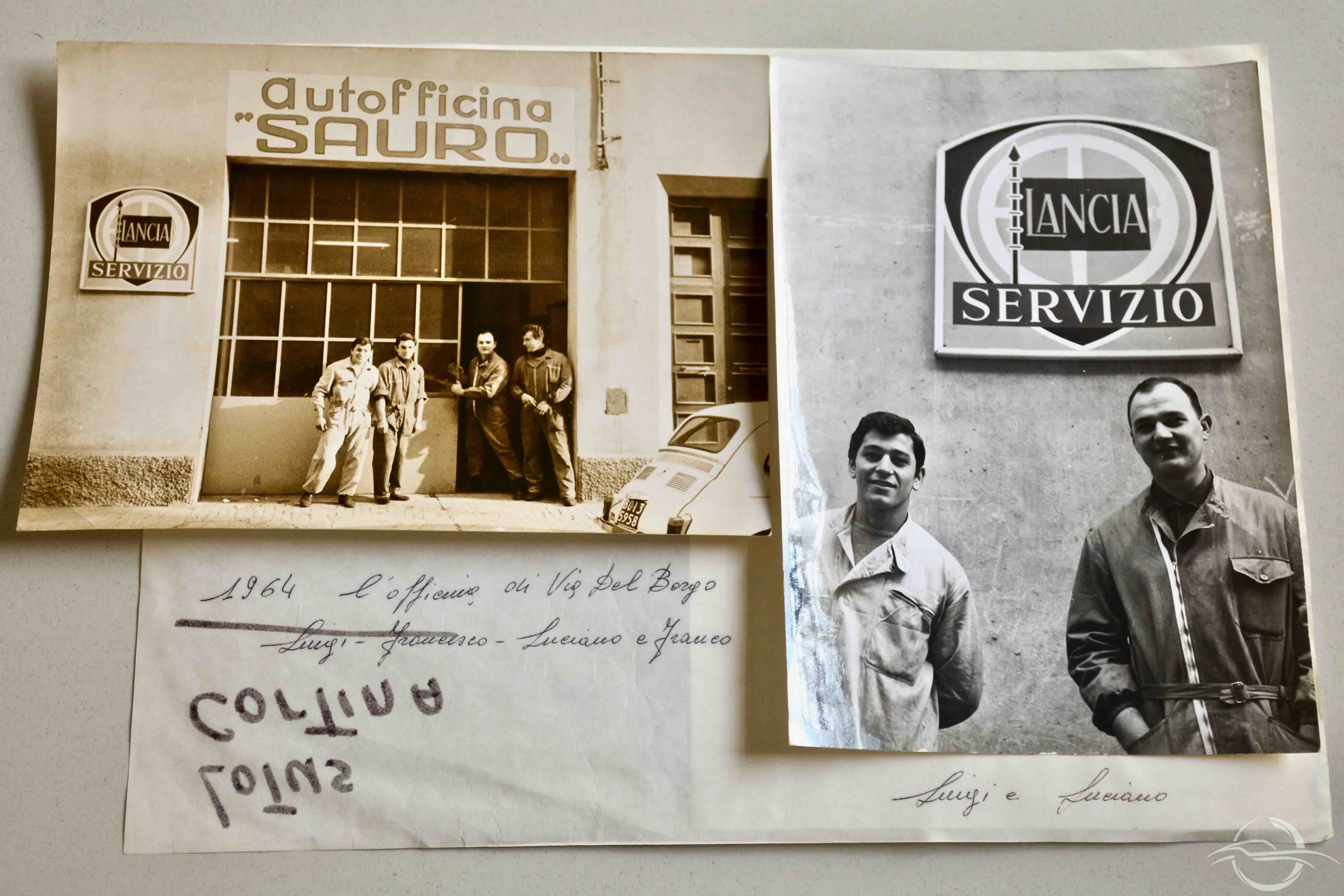

- Autofficina Sauro

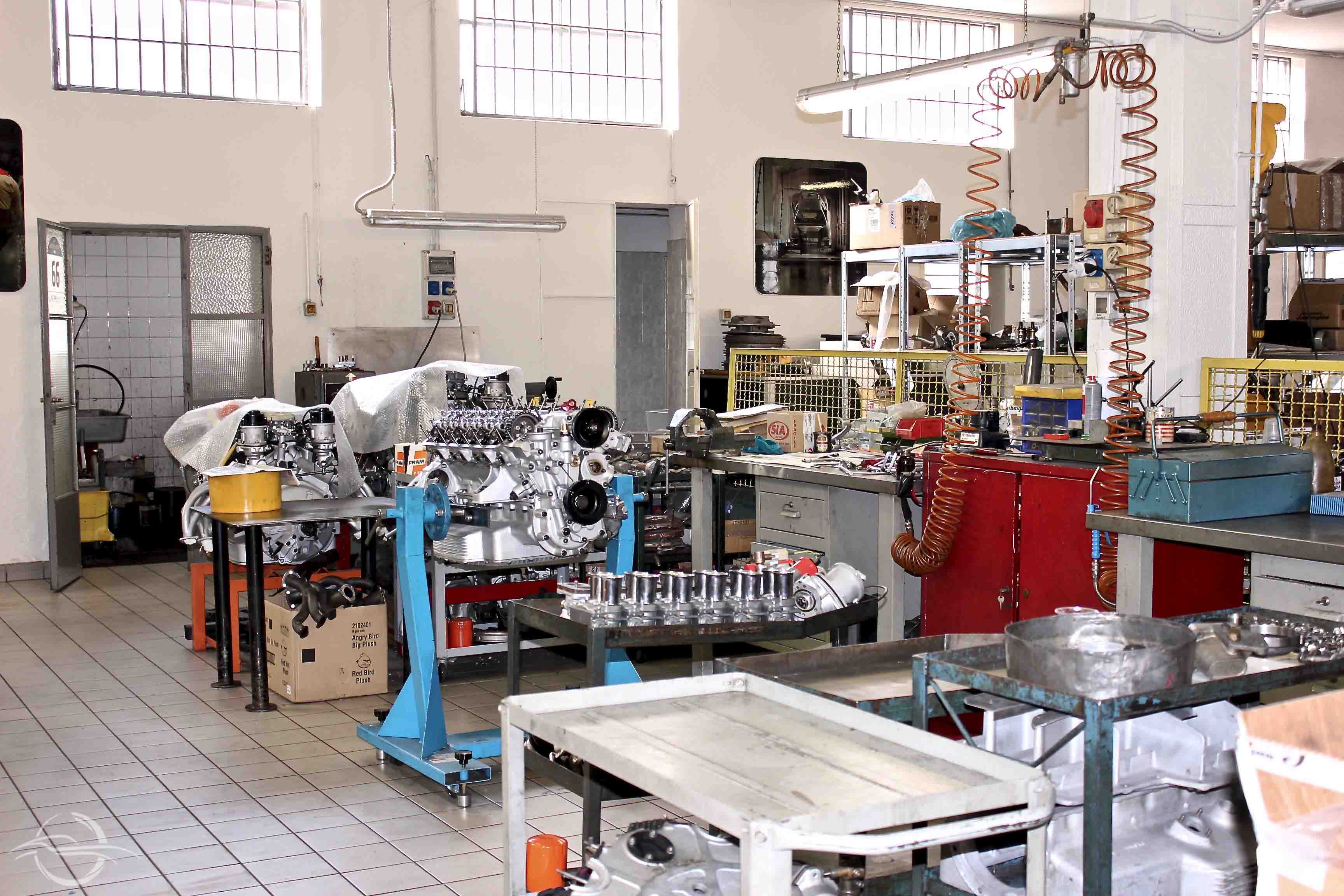

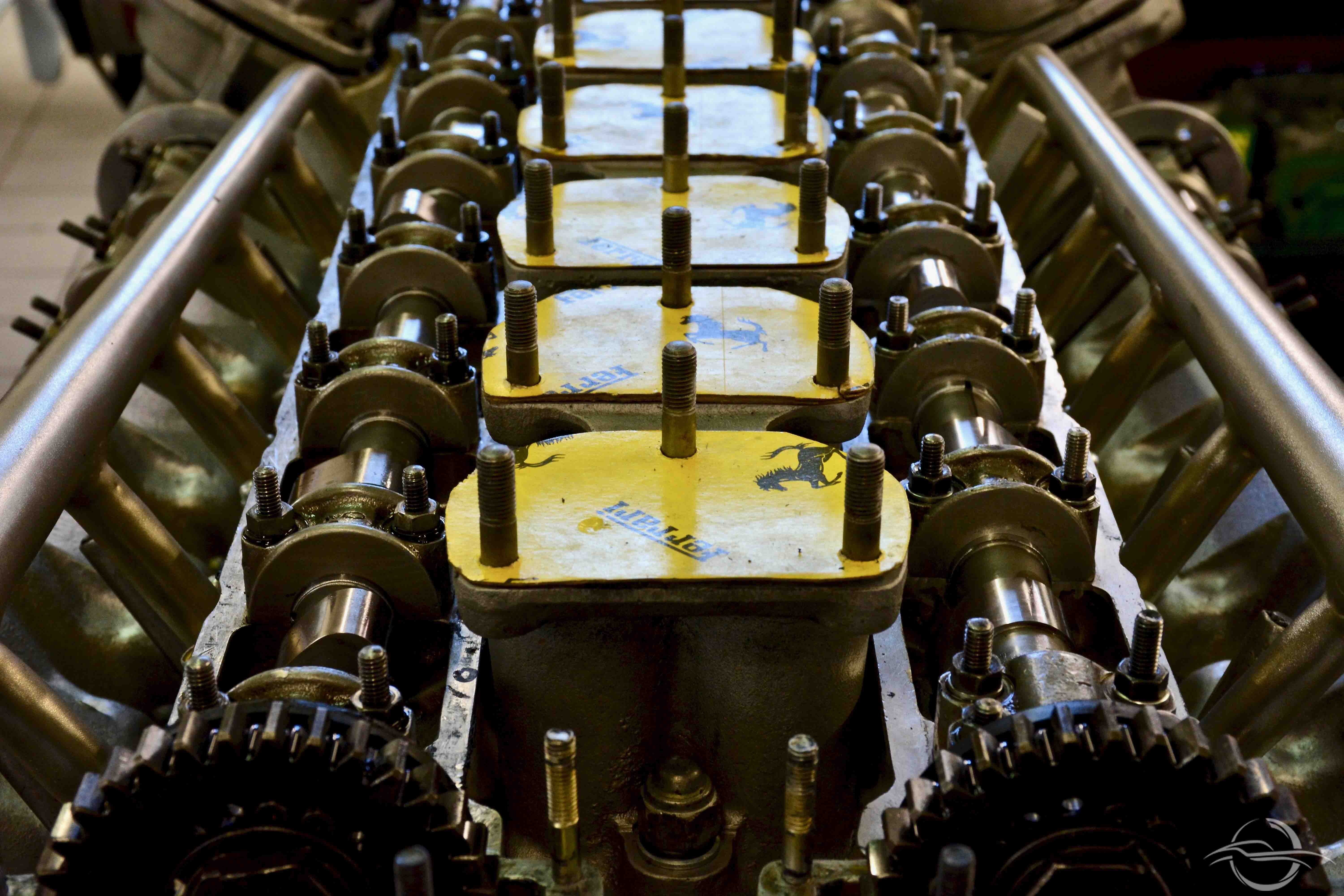

Engines are on the operating table shamelessly and they look like huge silver bowels. Further along, there is the department where his son, Francesco, works on the “modern” cars (which is how Rizzoli calls them).

And then there are the walls: white paper, a vertical world where old and recent photographs are displayed. This is exactly where at this work station, surrounded by photographic memories, Luciano Rizzoli talks about himself. The workshop is still named after his business partner, who accompanied him for nearly half a century: Sauro. Luciano points at him, on a photo.

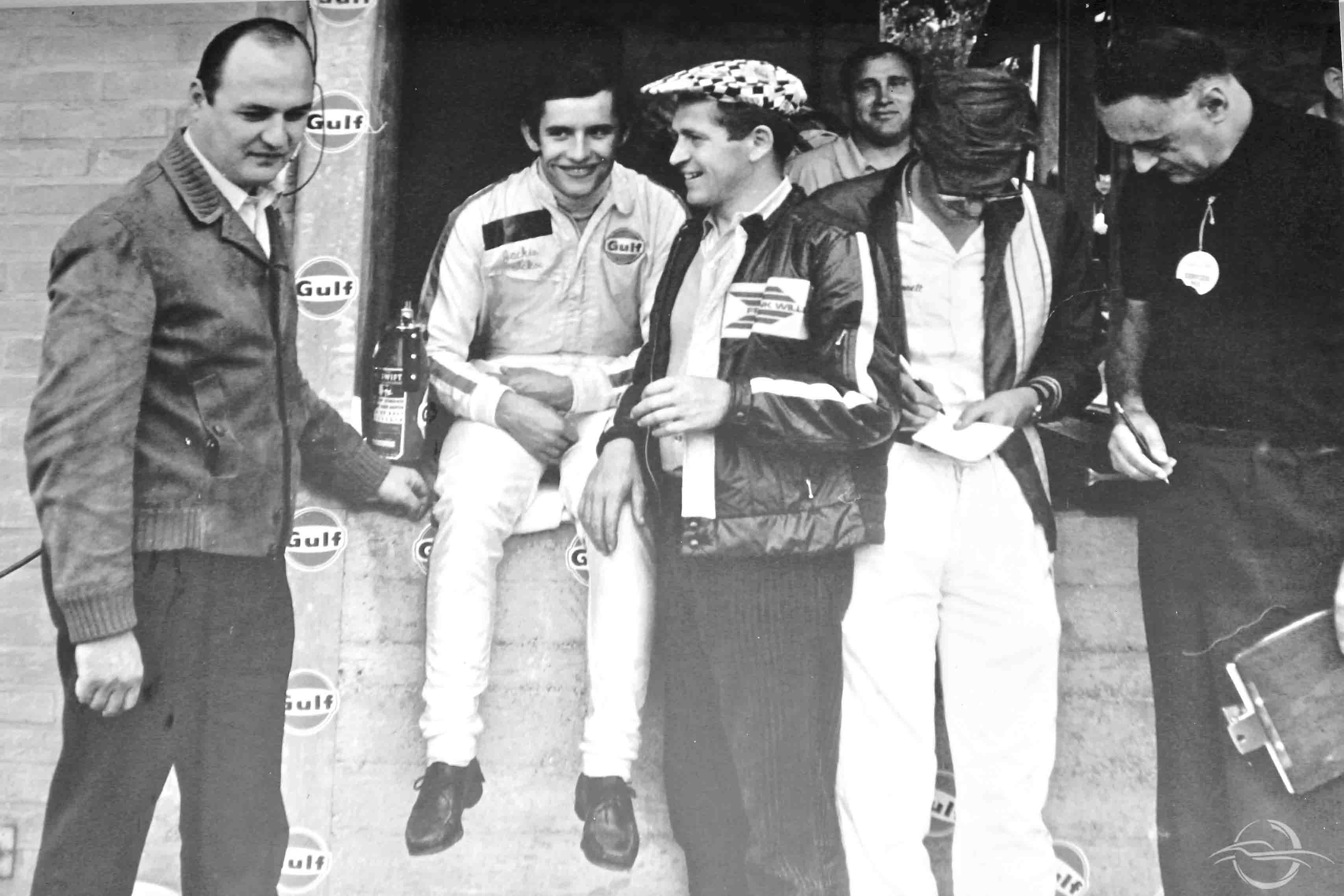

- Luciano Rizzoli, Jacky Ickx, Sauro Mingarelli, Ing. Mauro Forghieri

– This was my business partner, Sauro. He was the commercial soul of the business. We were very different, that is why our business worked so well for forty-six years. We completed each other: I worked peacefully and he took care of relations with whoever turned up. No, it’s not that clients bother me. I let them wonder, I’m pleased to have them around. Actually, I’m quite happy if the client wants to spend some time with me, following the job. I have quite a few clients like that! There’s an engineer, for example, who comes here as soon as he gets out of the office. I am four times twenty, but I am still pleased to come to the workshop in the morning. I am here from seven in the morning and I’ve been doing that every morning, for many years.”

Rizzoli doesn’t come from a family that worked in the business. His father worked in a foundry for forty years, at the time, being a smelter was no joke.

– It isn’t the same as it is now, where smelters have a glass cell and the work is all mechanized. My father worked with crucible: one held it by one hand, while the other one, like a fork, emptied the cast iron in the moulds. All of this process was done while wearing huge leather aprons, which helped you avoiding splatters.

– And how did you start working with cars?

– Well, probably my dad understood that they were my passion. Even back then, when we lived in the countryside and I was a little older than a child, the farmers brought me their Mosquito (the engine which used to be attached to bicycles) and I disassembled and fixed it. They used to pay me with pears if they were in season, or peaches if it was summer… that’s how it worked in the countryside. We lived in Bentivoglio, 12 km from Bologna. Do you know how many kilometres I cycled to get to Bologna? I used to cycle 12 km there and 12 km back. The day that I bought myself a moped, I told my bicycle: “I won’t see you again!” It was very cold back then… my mother made me two rabbit fur handles, to act as gloves.

– Those were the years of the war, weren’t they?

– Yes. I saw the war… now people joke about it and they talk rubbish, but believe me: war is evil. There was a little village by ours, Castelmaggiore, which had a major train station. The freight trains used to stop there, before they got to the city. During the war, the Germans stopped all of the passing trains and the Americans bombed the area. Do you know how the bombings worked? At midnight, the planes threw the signal down, which was such a light… as if it was suddenly midday. So my father used to grab me by my hand, my mother picked up my sister, and we ran to seek shelter in the fields. Afterwards, we dived in a trench, with metal sheets over our heads, in order to avoid the shrapnel. Saying that living in the countryside was by far better than living in the city… we didn’t go without anything. My parents had farm animals, but my grandparents helped us a lot during the hardest times.

– When did you leave the countryside?

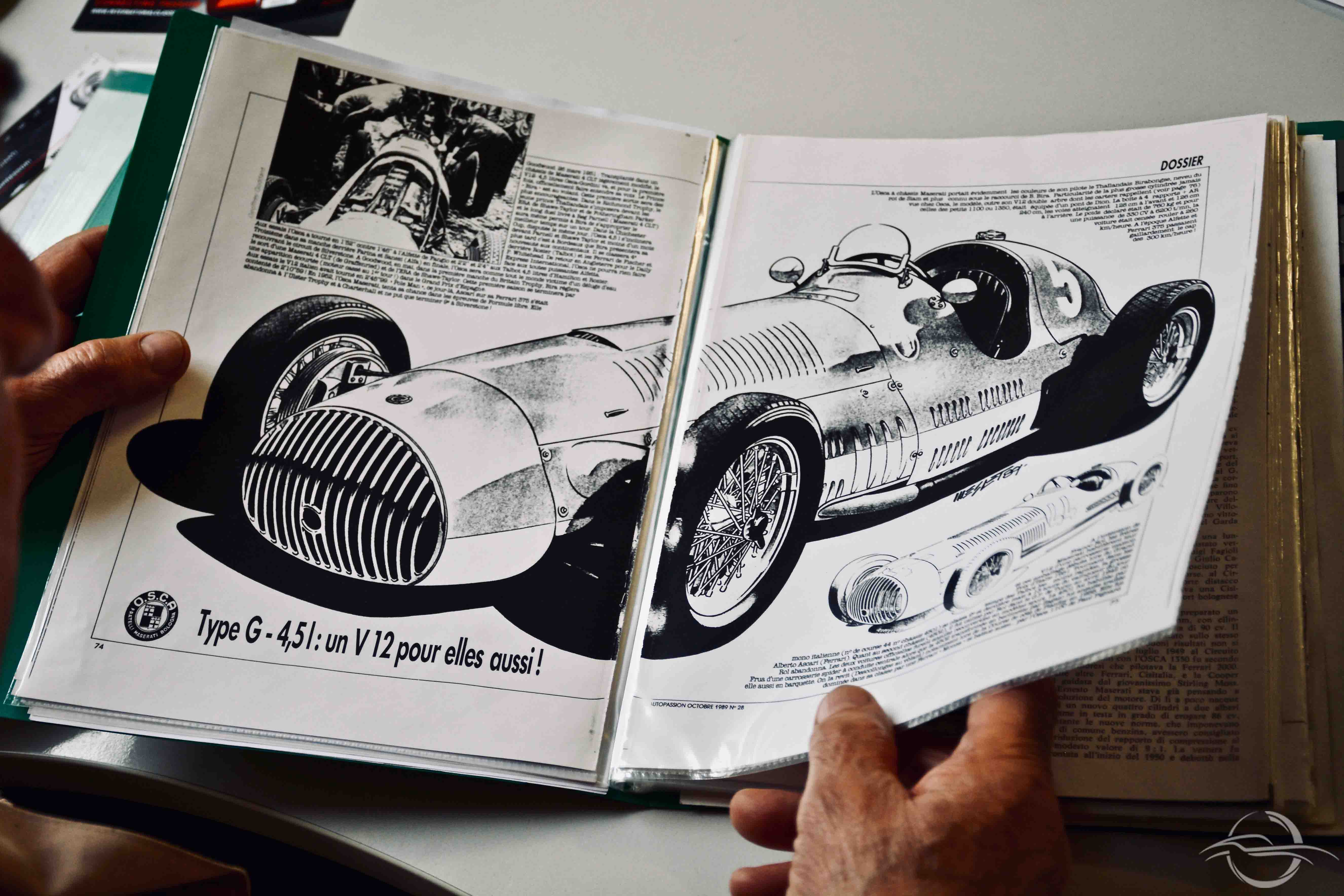

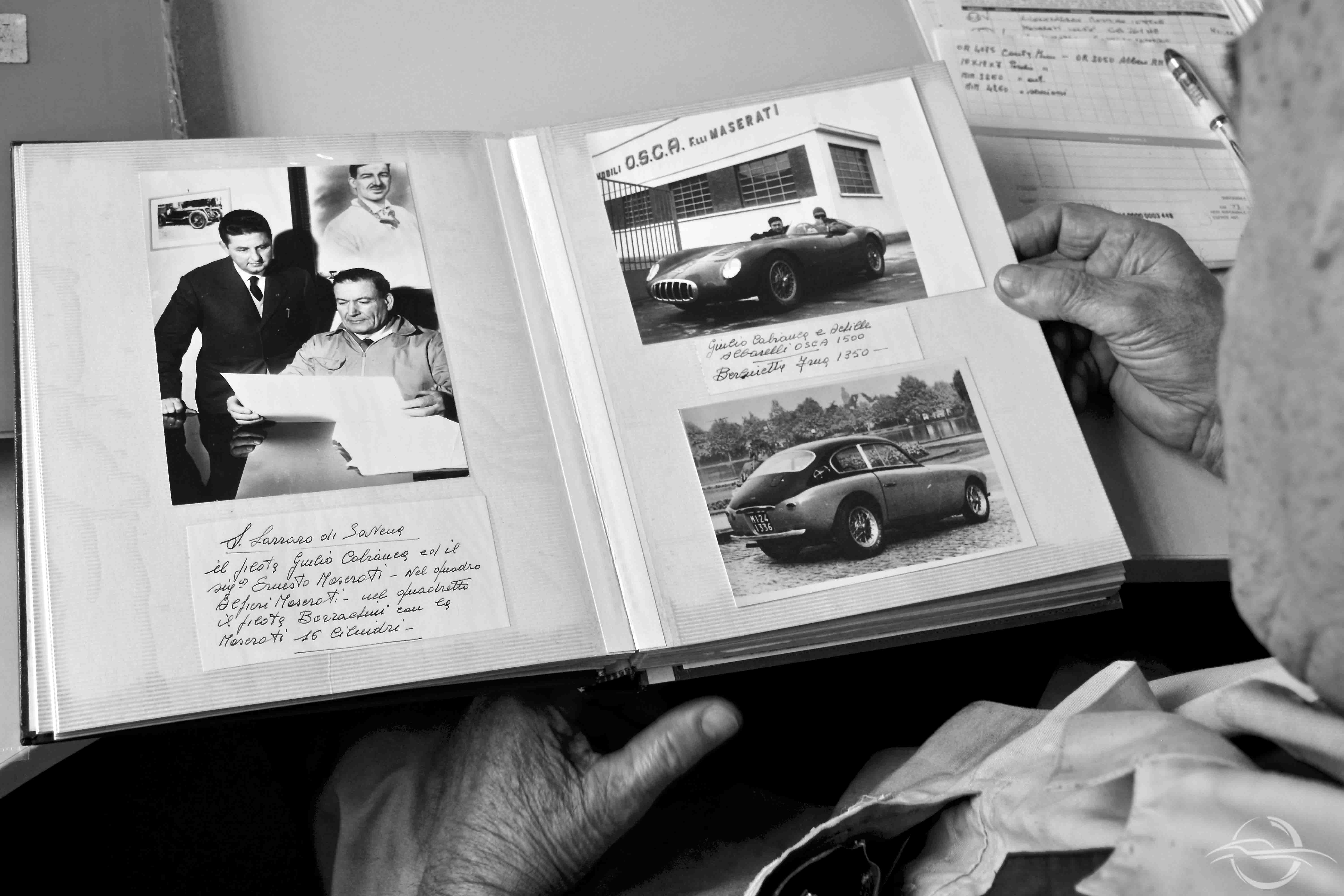

– Little by little. I finished school at 14. I still remember that day: it was the 15th of June 1951. In July, my father got me and took me to a garage in Bologna. There was a workshop there, where they prepared cars for the Mille Miglia, the real Mille Miglia: there were the Aprilia’s, the Ardea’s and the Aurelia’s… That’s how I started working. I used to be an errand boy… Learning wasn’t easy, because everybody was jealous and they kept their knowledge to themselves. It was right after the war, and there wasn’t much money around, but I was seeking stability. That was my first job. A year later, I found another workshop, where they provided assistance to the O.S.C.A. race cars.

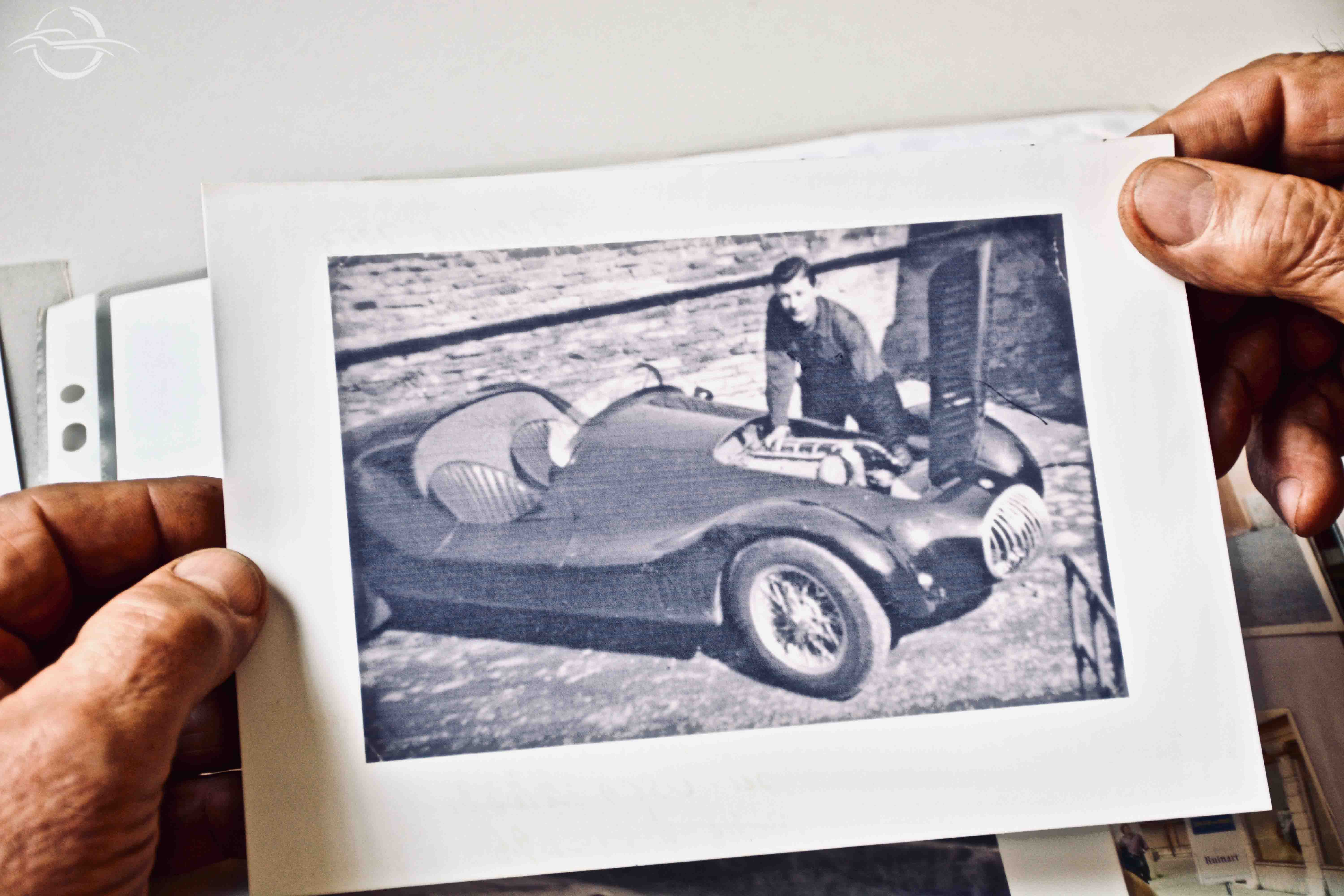

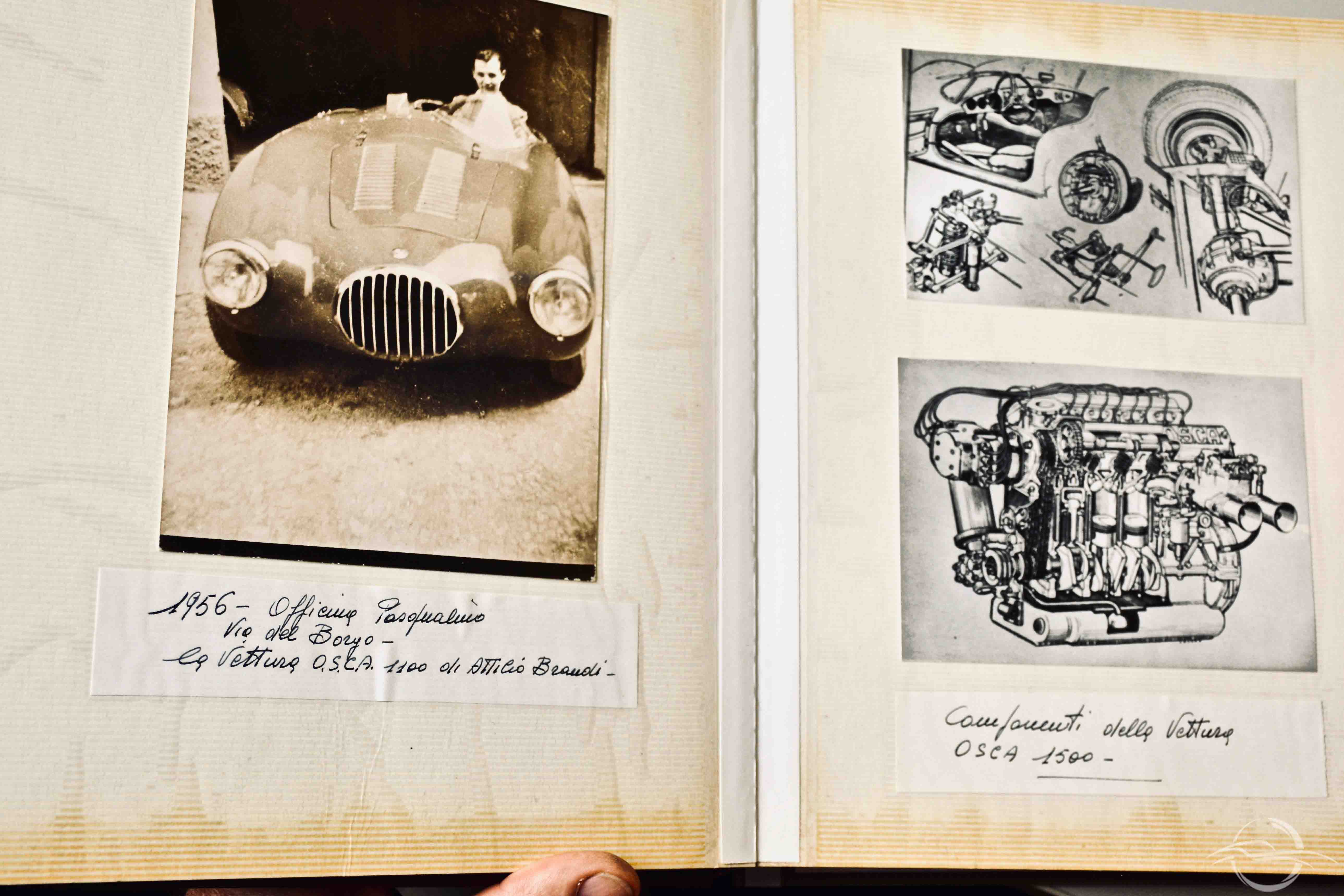

- Luciano Rizzoli – Pasqualino workshop

I was a little more than a child and, nobody trusted me of course. But my boss helped me a lot to understand how engines worked. For example, he told me: “Now we’ll fix the clutch.” And I started disassembling and touching all of the components with my own hands. Afterwards, we went to get the spare parts at the factory, the OSCA, which was here, in San Lazzaro, and then I re-assembled everything. I did everything while he used to watch me. He was my teacher, everybody called him Pasqualino.

Then, I attended some evening classes at the technical industrial institute Aldini Valeriani, where you learn mechanics. They had us disassembling airplane engines, of course, but they were still engines, and after having disassembled them, we had to re-assemble them. It’s easy to disassemble an engine if you throw it away afterwards, but if you disassemble it and then you have to re-assemble it, you must pay attention to what you’re doing.

I stayed there until I did the military service, afterwards, I started working in Ferretti’s Lancia workshop. That is where I met my business partner. When one day my boss proposed to me to take over the workshop, I thought about it and I made a decision. I was a little more than a kid and I was scared to take a step too far. Then, I discussed it with Sauro: things would have been easier with him. We opened the workshop in ’63. I was 26 years old.

Things started off smoothly straight away: Lancia Ferretti supported us and our business started taking off. Our workshop was small, but there were respectful machines in it. However, the turning point came later… and it was totally unpredictable.

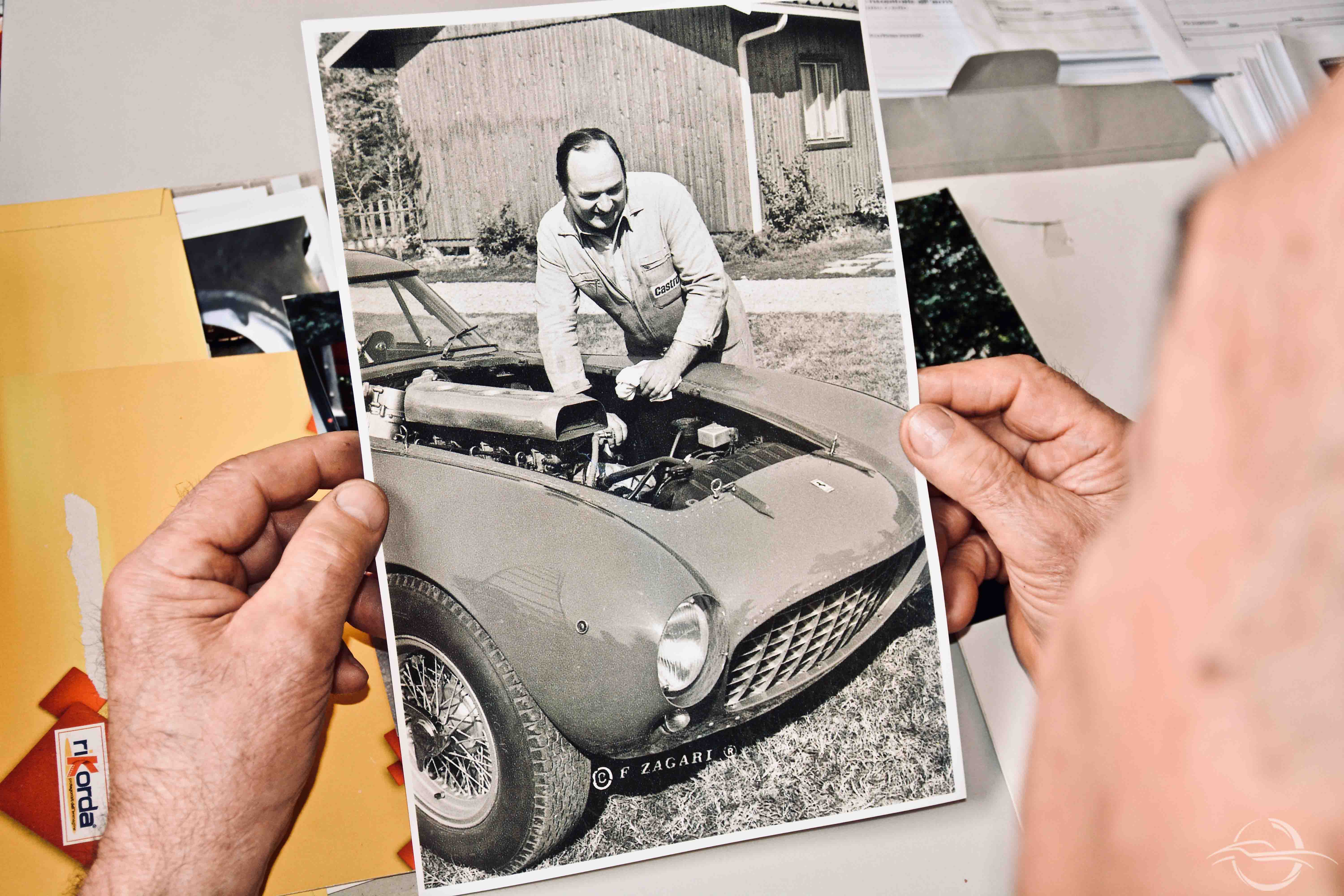

– One evening, the petrol station attendant came and asked us to lend him a hand. A man stopped by his garage who couldn’t start his Lancia anymore. I went straight there to check what was up. The car was a new Lancia Flaminia, with a San Marino registration. I started getting to work, I inspected the pumps, then I banged it slightly and there, the engine started again! So I took the car back to the workshop to take a general look at it. This man followed me. He looked around and it only took him a second to realise that the cars that we had weren’t simple economy cars. “Wouldn’t you be interested in servicing Ferrari cars?” He asked me, out of nowhere. So, caught unaware, I was a little baffled.

You know, in ’63, there were only two Ferrari’s in Bologna: one belonged to a pharmacist who never used it, and the other one belonged to another man, Conti, who later became the Dino Ferrari racetrack’s director. I mean, I didn’t know what to answer, especially I wasn’t sure whether it was worth it. I told that very honestly to this man, who, however, reassured me “Don’t worry, Ferrari is creating a car which will be successful.” This man turned out to be the Knight Commander Eugenio Dragoni, Ferrari’s sports director, who won the world championship with John Surtees. He was a passing client for us, we discovered later who he really was.

Two months later, we got a phone call, it was Enzo Ferrari’s secretary: “The Knight Commander would like to meet you”.

We turned up at Maranello and we didn’t have the slightest clue of what was expecting us. In hindsight, I may tell you that it was a very strange job interview, where we discussed everything, but nothing which concerned work. Ferrari talked to us about when he had the motorbikes team, he didn’t even mention cars. Nothing, in the end, he turned round and he told his secretary, in Modenese dialect: “let’s give the service to this guy.” We looked at each other blankly. Then he added, “what is your workshop’s name?” Outside, it said, “Lancia servicing”. “Well, we need to choose one yet”. And he told my business partner “Well, your name is Sauro, my horses are Sauro (chestnut) breed: let’s call it SAURO”.

He chose the name. That was better for us anyway, because if we chose a name which he didn’t like, we would have had to change it anyway. We got to the door and the Knight Commander calls us back. He looks very serious. “Hey, you two! Remember that a Ferrari is bought, not sold. Ferrari is a car which you buy as you wish to have it, not because you need it.

We only sell a second one if the service is good enough”. I don’t know whether that was a threat or a warning but we’ve been working for Ferrari for fifty years now… so it means that we did well enough…

– They say that Enzo Ferrari didn’t have an easy nature…

– Well, we always got on well with the Knight Commander. He used to call us once or twice a month, always around seven in the evening. “This is Ferrari. What do clients say about our cars?” He used to ask us every time, and we used to tell him which problems they reported, and he answered “We’re working on that, we’re working on it.

By International Classic, written by Martina Fragale

Keep following the story The Gentleman of the engines – Chapter 2

Read more

The Gentleman of the engines – Chapter 3