Scaglietti, a page of history

How important is historical memory? What is the ultimate meaning of “keeping”? For one of those many paradoxes which make life beautiful, we only discover that (or at least, especially) when facing death, destruction. When facing a cataclysm – human or not – which threatens our memories. It’s not by chance that the world is filled with museums from the twentieth century, the century that saw not only one, but two world wars!

I talked with Oscar Scaglietti about the importance of historical memory, he is very sensitive towards this subject and he is aware of the relevance and fragile beauty of memories. We also discussed the historical memory that rings them. Oscar talks about this – not by chance – mentioning exactly a cataclysm.

It isn’t the war, but a flood that made history: “When the ’67 flood happened, we had just moved to the building in Via Emilia – he recounts – the offices were below, in the basement and there we also had the archive with all of the car files from 1950. We always kept an extra key, as a service to our clients, should they lose theirs. With mud, the labels stuck to one another and it was no longer possible to distinguish which cars they corresponded to. We also had to go underneath the flood to recover the photographs. It was a very serious loss. It is something that we were not prepared to deal with. Most of Scaglietti’s historical memory was lost. Yes, historical memory is enriching: it’s a research tool for continuity. Everybody, even industrial giants, even a company like Ferrari, is lost with no historical memory”.

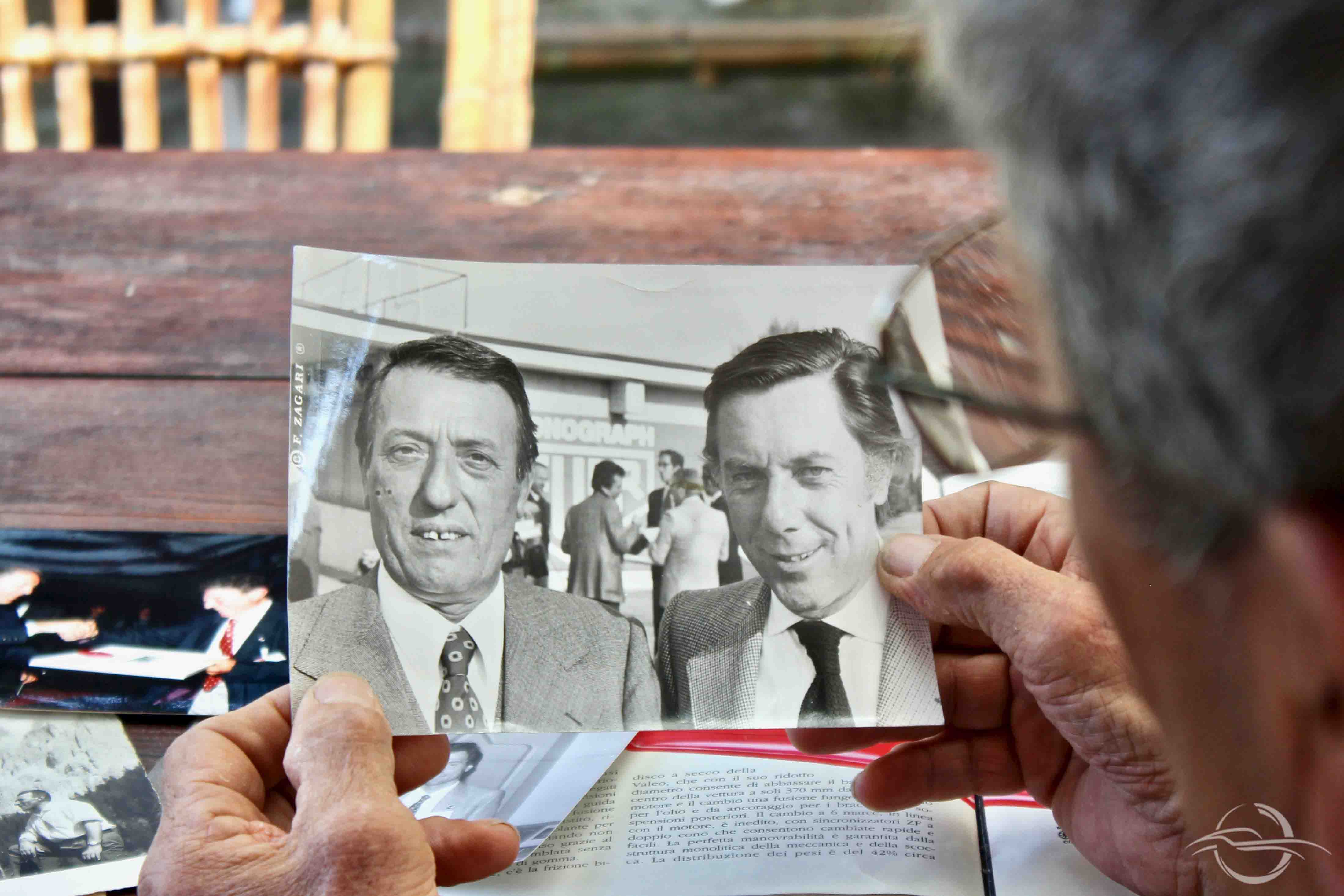

- Oscar and his father Sergio Scaglietti

While I listen to him, I remember that during our first chats, Oscar had mentioned the Modena exhibition. Now, while I relive the flood’s days through the emotion contained within his words, the idea of the exhibition is fuelled with additional meaning. Because an exhibition isn’t only a “podium” which celebrates the greatness of a myth, like the Roman’s triumph wagon. An exhibition isn’t only about parading (or parading yourself) but it’s a step of “keeping” through sharing. It’s a sort of memory album, browsed in public. I tell Oscar this thought and he nods.

We both – I gather that without asking him to confirm – think immediately about “ModenArt: Scultori in Movimento”, a beautiful event which was held last year, with the backdrop of the San Carlo church in Modena.

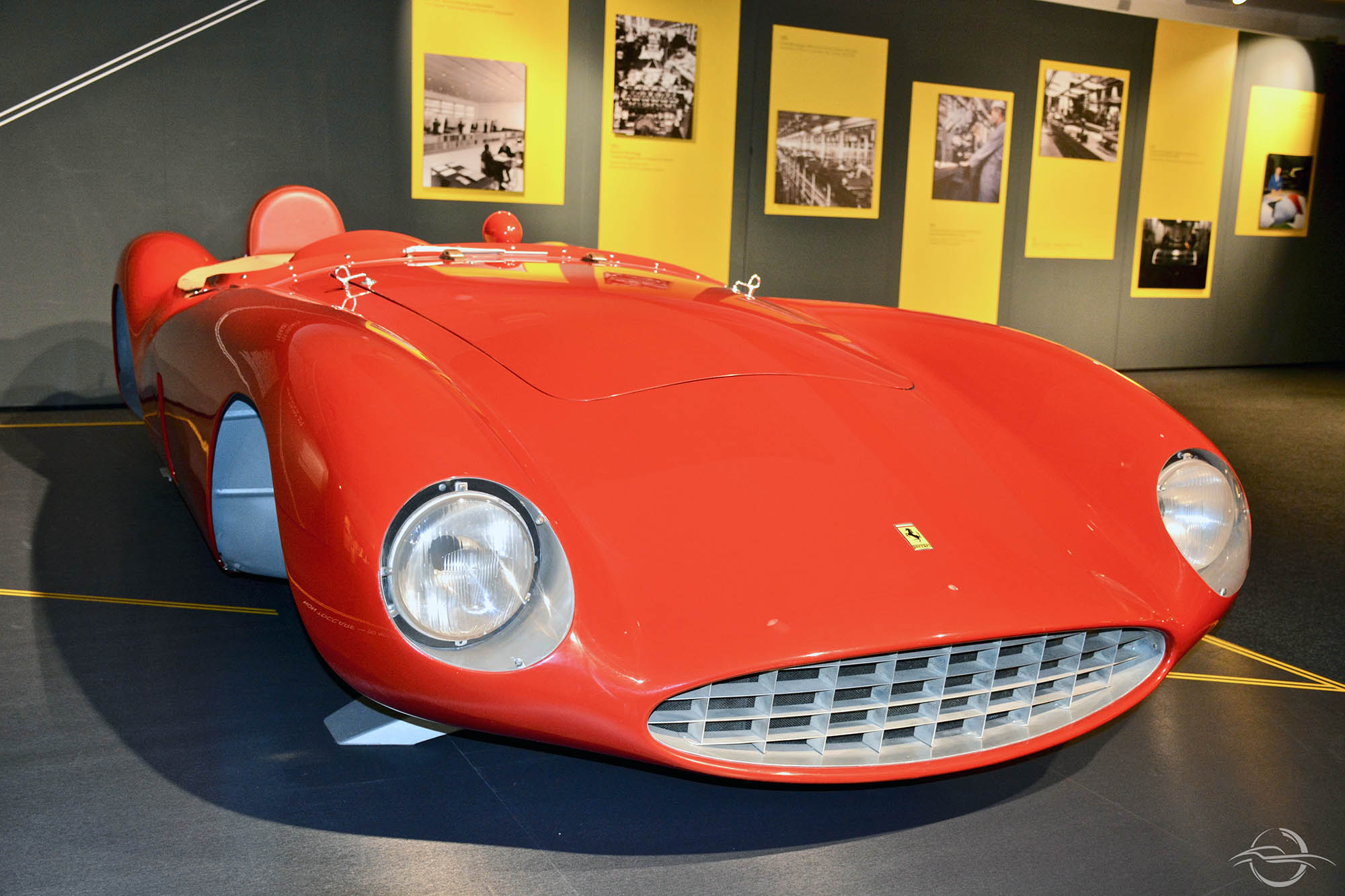

Impressive: the beauty of some cars which made history, nestled like a precious stone in the setting of an ancient church. You could admire eight mannequins at this exhibition, such as the prototype for the Ferrari 250 GTO from 1961, the GTO from 1962 and the one from 1964, the 500 Mondial, the 250 GT Nembo Spider, the Maserati 151/3 and the Cobra Daytona. We’re talking about historical cars; it is obviously astonishing to notice how the line of the cars represents something powerfully modern in such a classic setting. This makes me think about Marinetti’s “All’automobile da corsa” poem: old and yet futuristic at the same time.

I attended the inauguration too: it was lovely to see Gian Carlo Guerra and his wife, Maria, once again! That first interview with Mr Guerra, which we were the first to publish, is still in our hearts, but not only. “You have invaded my house!” Mrs. Maria remembered with entertained eyes. I smiled and I thanked her once again. The truth is that on that day – the inauguration day – I was a bit moved. I had seen Oscar and Gian Carlo Guerra embracing each other and crying, and I was well aware of the events which had undermined their relationship many years ago (when Mr Guerra went to work for Lamborghini). I couldn’t ignore the importance of that moment.

The automobile world isn’t only the reign of cars but it is also – and especially – a net of relationships, meetings and clashes, and it’s as if ModenArt had recomposed the threads of many plots, bringing many of the characters back together, on the same stage. Oscar embracing Guerra, indeed, and Guerra with his protégé, Egidio Brandoli, and with Afro Gibellini and Oriello, his pupils par excellence. “With many, but very many former Scaglietti employees, who are all electrified by the event” remarks Oscar proudly.

- Egidio Brandoli and Gian Carlo Guerra at ModenArt, San Carlo church in Modena, pic by Angelo Rosa

I have no difficulty believing in this. The creation process bringing to the birth of a car, is (I guess) a sort of collective gestation, where I believe each one feels like an interested party. Besides speciality, which certainly each artisan has within a factory, and which conveys meaning to their role and their “being there”, I believe that the key difference against the “assembly line” as it is commonly understood, is actually the bond between each one of the parties that participated in the birth of a car and the final product. Therefore, in a certain way, the non-alienation of the artisan from their work. When facing some beautiful cars standing out against the Modena church, I wonder – actually thinking about the perfection of the final product – which were the steps of the germination and production process which led, step by step, to the birth of a new car. I bounce the question back to Oscar.

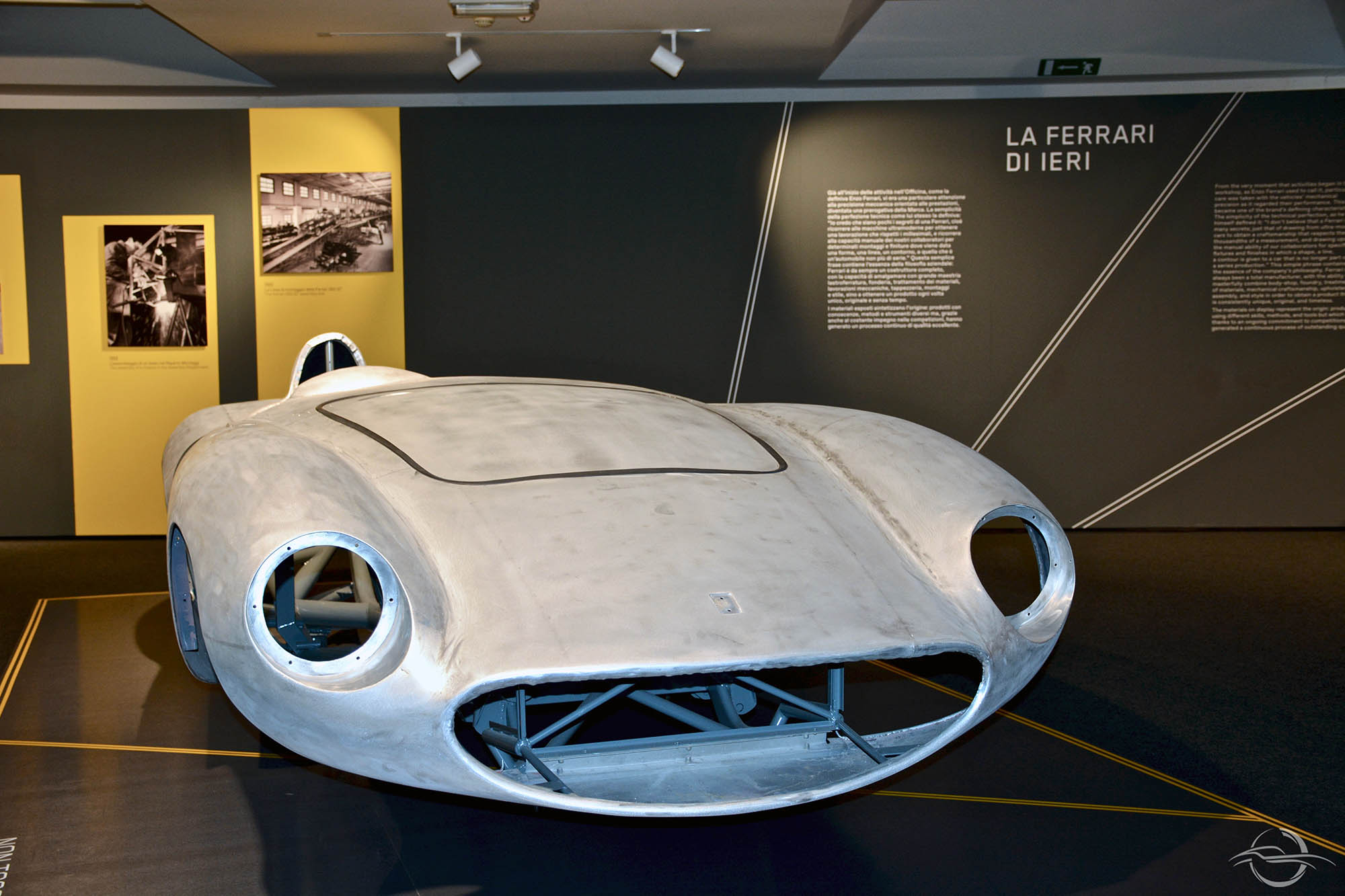

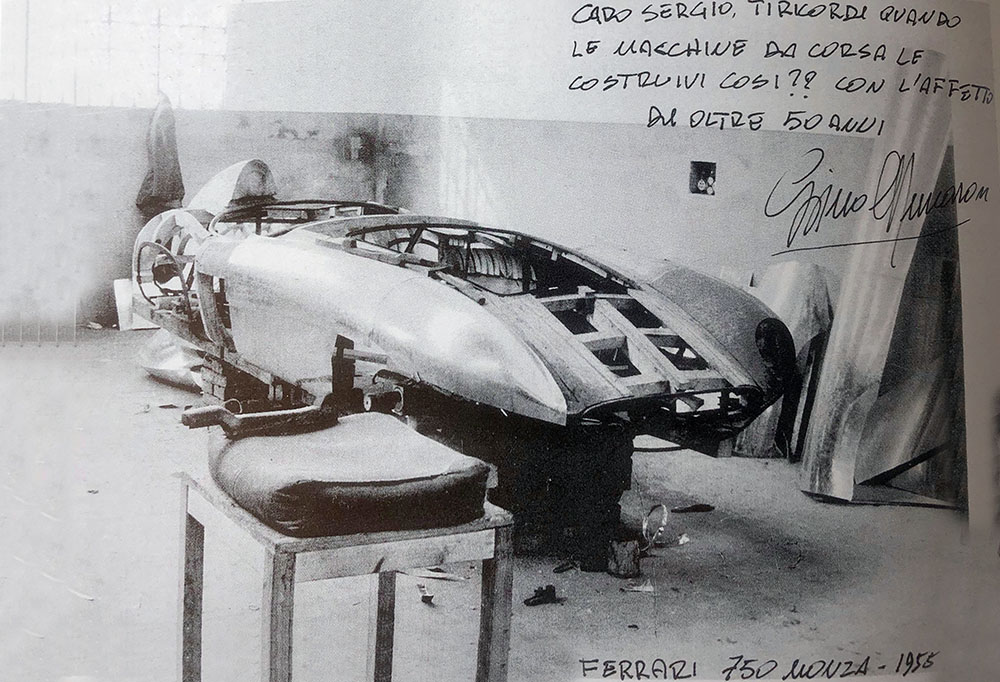

– Can you tell me about how cars were born, in your company? When looking at these photographs, it feels strange “to go back to basics”, that is, that poor and essential structure which you implemented in your workshops.

– Yes, initially it was truly about a poor and bare structure. My father had started with aluminium cars for competitions. Initially, cars were in bare, raw aluminium and many used to say, “Come on Sergio, do you really want them to be so bare?”. This is why my father started to varnish them at least, but only externally.

– And what about the interiors?

– The interiors were unrefined, with blue fabric seats and that’s it. Then, a few clients wanted leather seats because they sweated less, so we started to customise them based on the requests.

– As a matter of fact, I guess that you based yourselves on some very concrete principles.

– Sure. The new car was born from the needs dictated by regulations and our duty was to dress it in the lightest and most appropriate way for races: the goal at Scaglietti’s was to create the lightest and most competitive car overall.

– Your priority was the races then.

– In some cases, we studied a car which could be good for both racing clients and traditional clients. This is what happened with the Ferrari 250 GT Berlinetta, known as Tour De France and designed by Pininfarina. It was made in aluminium and we delivered it to the customer ready to race, we restricted the kilos by using the lightest and cheapest materials. Whereas, for luxury clients, who wanted the same car, we produced them in sheet steel, we inserted the leather interiors and dashboard.

- Ferrari 250 GT Berlinetta TDF at Ferrari Maranello Museum

– So, as far as the production of racing cars was concerned, your keyword was “lightness”.

– Yes. Even later, when Ferrari decided to separate the production model department from the racing department, our main research was actually based on this presupposition: to lighten up cars, to make them able to fly. I mean, our goal was literally to put wings on your feet (actually, on your wheels). In order to do that, we had to work where the extra kilos lay: the boning of the seats, the interior upholstery of doors, on dashboards. It was an actual hunt, we couldn’t get rid of the engine or piston rods, but we searched all around those, we searched for the extra gram!

– And with production cars, what were the key principles that you focused on?

– When we started manufacturing production cars, with my father, at Scaglietti’s we looked mainly at functionality: that everything was easily usable. From 1965 onwards, the customer support service had to intervene promptly, we knew that we couldn’t throw away hours of work for a couple of screws! Therefore, if the auto electrician or the upholsterer intervened, they couldn’t revolutionise the car.

– What was your relationship with the designers like?

– There was a very close exchange with them. The new models were born from the collaboration with the designers, with Pininfarina – for example – we had a dual thread relationship. I was available most of the time and then, depending on the project, either Gian Carlo Guerra or Afro Gibellini came to do their job.

- Sergio Scaglietti and Sergio Pininfarina